Time Isn't Money

What do you want, your time or your money?

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

If you were one of my first 200 readers, you may remember my first article: Time Isn't Money. Since there's now 4,100+ of you (which is still crazy to me), I wanted to revisit this idea.

Remember that time is money. He that can earn ten shillings a day by his labour, and goes abroad, or sits idle one half of that day, though he spends but sixpence during his diversion or idleness, it ought not to be reckoned the only expence; he hath really spent or thrown away five shillings besides.

Ben Franklin

Ben Franklin coined the term "Time Is Money" in his 1748 essay Advice to a Young Tradesman.

Franklin intended to convey the monetary cost of laziness by pointing out that when one is paid for the amount of time one spends working, minimizing non-working time also minimizes the amount of money that is lost to other pursuits.

I have to disagree with the Founding Father on this one, though.

Time isn’t money at all. It’s something much more valuable.

Time and money are engaged in a constant game of tug-of-war in our lives. We sacrifice time to gain money. You work forty hours a week to get a $1200 paycheck. You give up your Saturday morning to make extra money mowing lawns. We then turn around and spend our money to gain more time.

You spend $2000 on a week-long vacation in the Florida Keys. You pay a maid $500 to handle your household chores. Why? To free up your time. Then the cycle repeats.

We often treat time and money as equals, but they aren’t, for two reasons.

Money has diminishing marginal utility

Time is finite, money is infinite

Diminishing Marginal What?

If you took an introductory Econ class in college, you’ve probably heard the term “diminishing marginal utility”. If you’re unfamiliar, marginal utility is the additional utility, or enjoyment, gained from consuming an additional unit of something. The classic example goes something like this:

When a hungry consumer eats one piece of pizza, they gain a ton of utility. However, as they get full, the satisfaction from each additional slice gets lower and lower.

That first slice of pizza is fantastic. You hadn't eaten all day, and that steaming triangle of pepperoni and cheese never looked better. The second and third slices are still good, but not nearly as satisfying as the first. By the time you finish the whole pizza, you are stuffed. There's no additional utility from an 11th piece. If anything, you're pretty disgusted that you crushed a whole pizza by yourself.

Money works the same way, though we rarely think about it in these terms. We are constantly focused on what we could do with a little bit more money.

“If I get this raise, I can afford that beach house in Florida.”

“If I close this deal, I can finally pay for that trip to Hawaii.”

“If I make partner at my firm, I’ll be set for life.”

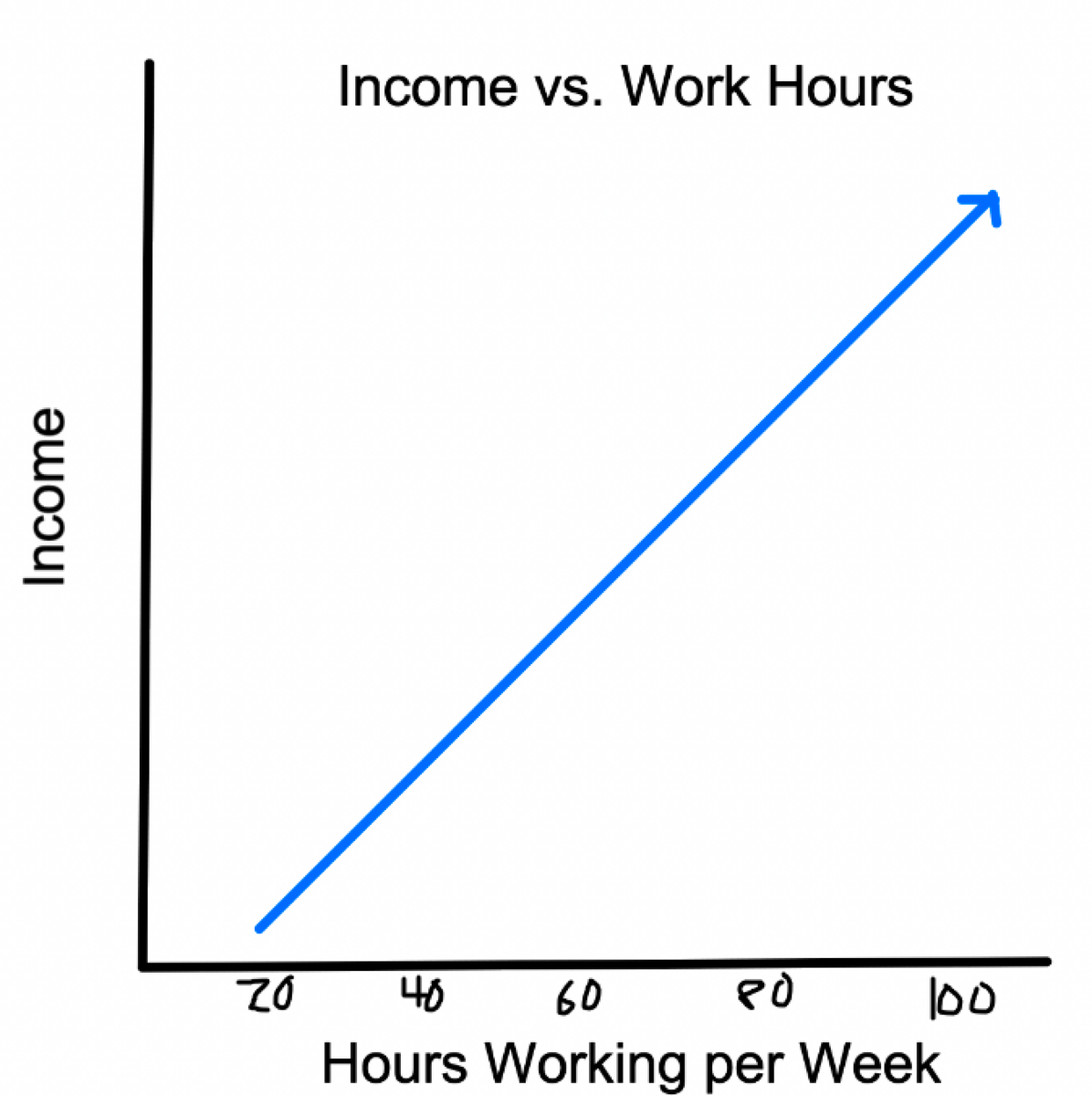

We have this 1:1 perception of income and satisfaction. If I make X amount of money, I will receive Y amount of satisfaction. Our idea of the income and life satisfaction graph looks something like this:

We think that quadrupling our income will quadruple our happiness, but that’s not true. Don’t believe me? A study by Purdue University determined that happiness derived from additional income flatlines after $105,000.

How does income really relate to satisfaction? Check out the graph below:

Diminishing marginal utility.

If you stop and think about it, it makes sense. Additional dollars have an outsized impact on your lifestyle when your income is lower.

Say you make $30,000 a year in Atlanta, GA. If your rent and utilities are $1,000 a month, it’s going to be a struggle to cover your bills, put food on the table, and have money left for anything extra. Now bump your income up to $50,000, and you can live pretty comfortably. You may not take lavish vacations or sit court side at a Hawks game, but you won’t lose sleep over next month’s rent.

Now scale up to $100,000 a year. Take out $25,000 for taxes and $12,000 for this year’s rent and utilities. You have $63,000 leftover for whatever you want. Want to go skiing in Park City? Sure. Two weeks in Europe? Why not. Season tickets for the Braves? No problem. You won’t have a Ferrari, vacation home in Aspen, or private jet, but you can afford pretty much any activity you want.

As your income scales up from here, you can buy bigger houses, nicer cars, fancier meals, and better clothes, but you can’t go anywhere or do anything new. You just spend more money on upgraded experiences. If you can cover your bills, spend money on experiences, and save/invest the rest, you are in a great place. Everything else is extra.

There is actually a paradox associated with having extravagant amounts of wealth:

Some luxuries won't make your life any better, but losing them after having experienced them will certainly make your life worse. - Nassim Taleb

Time, the X Factor

So you derive a little less satisfaction from each additional dollar. Who cares, as long as you’re still gaining something, right? That’s where Father Time comes in. If you want to make that extra dollar, you probably have to give up some extra time. Money and happiness aren’t linear, but income and time are.

Maybe you work a 40 hour work week and get paid $65,000. You never have to work overtime, and you never have to work weekends. Meanwhile, your cousin is working in investment banking. He makes $200,000 a year. However, he’s working 8 to midnight half of the time, and he has to be on call most Saturdays. Yeah, he’s making a lot more money than you.

But what about his time?

As humans, we spend a lot of time fantasizing about that next job. Next promotion. Next pay raise. But we rarely think about what we’re giving up: time.

Opportunity costs drive every decision that we make. Choosing one career is not choosing a dozen others. Choosing one partner is not choosing a million others. Choosing to do something one day is choosing not to do countless other things.

The most powerful opportunity cost in the world is what we choose to do with our time. Once those hours, days, weeks, years, are gone, we don't get them back.

To summarize the relationship between our time and our money:

If you live 90 years, you have 4,680 weeks on this planet

Each additional dollar earned will require additional labor (time)

Happiness derived from each additional dollar quickly drops after $100k income

How much of your limited time are you willing to sacrifice for unlimited money? How much of your life will you give up to increase your net worth?

Let's flip the question around: How much money would Jeff Bezos give up to be 25 years old again?

How much are all of those billions really worth?

Three Thoughts

I have drawn three conclusions from this relationship with time and money.

You need to find your "enough"

You need to invest

You can always make more money

Enough

Enough is a dynamic number that varies from person to person. It even changes within one person's life as their circumstances evolve.

Maybe enough means $100k at 26 when you're single, and $250k at 35 when you have two kids. Maybe you want to take expensive trips, or buy a beach house. Maybe you live in an expensive city, or cheaper suburb.

The number behind your enough is less important than finding your enough itself, but finding your enough is critical. There is no upward limit to how much money you can make, which makes it all-too-easy to fall into the trap of chasing every extra dollar at the expense of your time. Enough tells you the level where you can focus less on making more money, and focus more on how you spend your time.

Invest

Investing is the best way that we can create more time, because investing grows our money without us having to sacrifice time. With your capital invested in the stock market or real estate, you can do whatever you want from day-to-day and sleep easy knowing that over time, you will grow wealthier.

Investing is the strongest catalyst for securing one's freedom as quickly as possible, and investing works best when utilized early and often.

If you are aware of your enough, and you aggressively invest every dollar that you don't need, you can grow your capital quickly while optimizing for the life style that you desire.

If you are obsessed with chasing every additional dollar, and spend every penny that you make on frivolous things, you'll find yourself a slave to your income, never able to escape your job.

Just Make More

It's important to find your enough so you don't sacrifice your time for dollars that won't improve your life. However, minimizing every expense can be detrimental as well.

Money has unlimited upside; there is no ceiling on your potential net worth. You can only cut so many expenses though. At some point, you will have to pay rent, eat food, and cover your transportation. Taken a step further, you shouldn't have to skip out on weekend activities with friends and family, or avoid taking vacations, in the name of "budgeting".

I want a life that is rich in experiences, and sufficient in finances. Being the richest man in the world isn't important to me, but doing a lot of cool shit is. Guess what? Cool shit costs money. And I'm not going to sacrifice incredible experiences for the sake of saving money. After all, the whole point of saving money is to spend it on something. Saving for the sake of saving has minimal benefits after a certain point.

The optionality of your money decreases as you get older as well.

$1000 spent on a roadtrip with friends in your 20s could change your life. Is that money going to be better spent when you are 90 on your death bed? No one gives a damn about who has the most expensive funeral.

Make the money that you need to afford the experiences that you desire.

Wrapping Up

Money is infinite, time is finite. These are the two rules of the game. To maximize your satisfaction from the game, you need to know how much money is enough, you need to make money without sacrificing time, and you need to be able to afford the experiences that you want in life.

Spend all of your money? Go make more. Spend all of your time? Rest in peace.

The clock is ticking.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!