Performative Grind Culture and the "9-9-6"

Plus: Gen-Z's nihilism problem and a few other links.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

“Yeah, but how hard are you working?”

Burning Man came and went last week, and according to this article by the San Francisco Standard, the crowd keeps getting older and older. The reason? All of the Bay Area zoomers have exchanged alcohol and ecstasy for “lifting heavy” and “9-9-6” work schedules.

In previous eras, Burning Man meant the clearing out of techies from the Bay Area in favor of a week on the Playa. However, more and more local startup founders and investors are now choosing to skip the annual pilgrimage.

“The culture has shifted,” said Jenny He, founder and general partner at Position Ventures. “A lot of young founders I know don’t really drink or party. They’re heads down working long hours, building brands, and creating content.”

Daksh Gupta, the 23-year-old cofounder of AI code review Greptile, said Burning Man hasn’t really been part of the zeitgeist since he moved to San Francisco in 2023.

Gupta, who has become a poster child of AI boom’s grindcore culture, summarized the current mood among young tech workers in San Francisco as incompatible with the Burner sensibility: “The current vibe is no drinking, no drugs, 9-9-6 [work from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week], lift heavy, run far, marry early, track sleep, eat steak and eggs.”

The 9-9-6 rise-and-grind ethos is very much a thing in the SF tech scene right now. Water and tea at happy hours, “cracked engineers” coding away deep into the night, all in the name of B2B SaaS, or building AGI, or whatever. While there are exceptions, I think much of the “being seen grinding late into the night day-in and day-out” is a bit performative in nature. It also hinders, not helps, a company’s performance in the long-run.

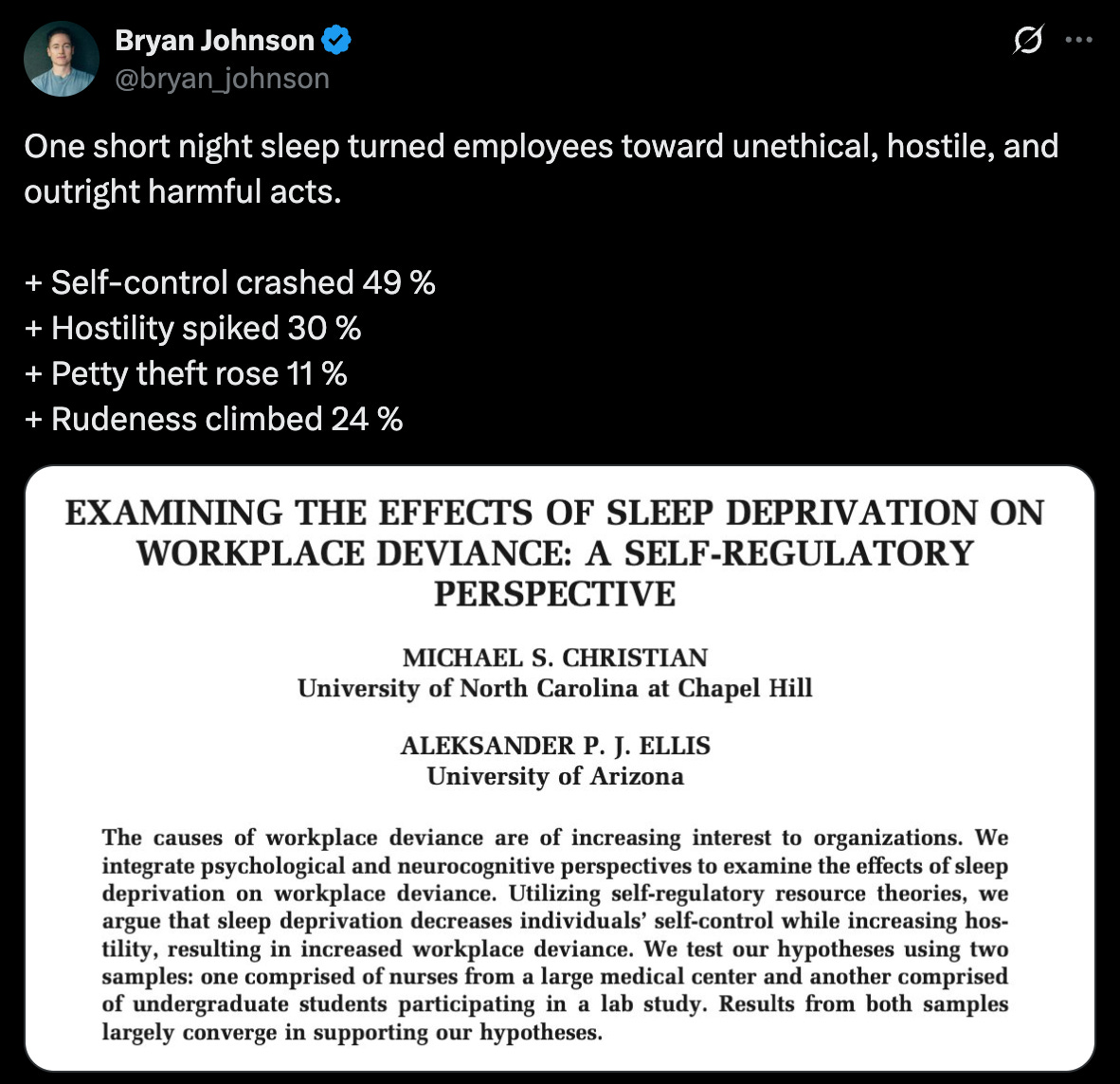

Bryan Johnson, aka the “Don’t Die” guy, has tweeted hundreds of times about the value of quality sleep, and the detrimental impacts of not getting enough sleep. I’m not a “don’t die” disciple, but considering that Johnson has been meticulously measuring the impact of sleep on his cognitive performance and mood for years, I trust him on this one.

The good news? This lifestyle isn’t necessary to do good work. In Cal Newport’s newsletter this week, he shared a valuable highlight from one of his old blog posts from 2008:

I found writing my thesis to be similar to writing my books. It’s an exercise in grit: You have to apply hard focus, almost every day, over a long period time.

To me, this is the definition of what I call hard work. The important point, however, is that the regular blocks of hard focus that comprise hard work do not have to be excessively long. That is, there’s nothing painful or unsustainable about hard work. With only a few exceptions, for example, I was easily able to maintain my fixed 9 to 5:30 schedule while writing my thesis.

By contrast, the work schedule described by the anonymous grad student from above meets the definition of what I call hard to do work. Working 14 hours a day, with no break, for months on end, is very hard to do! It exhausts you. It’s painful. It’s impossible to sustain.

I’m increasingly convinced that a lot of student stress is caused by a failure to recognize the difference between these two work types. Students feel that big projects should be hard, so hard to do work habits seem a natural fit.

For context, Newport has collectively sold well over 2,000,000 copies of his eight books and counting, he produces a weekly newsletter and podcast, and he has been a tenured computer science professor at Georgetown since he was 33. Not bad for someone who sticks to a 9-5! The differentiating factor (as noted in his blog post) is focus.

I’ve gone through short stretches where extended hours were required to finish a project (like locking myself in a hotel for two weeks to write a book), but those occurrences are outliers, not norms, and even that was more a consequence of extended procrastination than some inevitable outcome that couldn’t be avoided.

Most of the “9-9-6” 12-hour daily grind is, in my opinion, a consequence of context switching, procrastination, waiting on replies/feedback from others, and doing things that “look like work” than it is a requirement for quality results.

Tell me if the following situation sounds familiar:

You start off researching a company or industry, you see a relevant tweet, then, 27 minutes have gone by before you realize you were absentmindedly scrolling. Oh, and you have a series of six tasks to complete today, and you get 60% of the way done with the first, but then you check your inbox, and there’s an email that you “have to respond to right now” (you don’t), which breaks your concentration, and there goes another 20 minutes of cognitive offloading and onloading.

And maybe after sending that email, you start working on another task on your to-do list instead of resuming the first one, and at the end of the day you have a half-dozen things that you’ve sort of done, none are near completion, so, even though it’s now 6:00 PM, you sprint through tasks 1-3 to at least complete something that day, and you wrap up around 8:30. I mean, sure, you “worked” ~12 hours, but the last two hours were more valuable than the first ten.

I would be curious to see how much of a typical “9-9-6” is spent procrastinating, context switching, and “attempting to work,” rather than doing the work itself. In my experience, focused blocks of work can give you the same results much faster (plus, it leaves you time to touch grass).

What I’m Working On:

In 2020, Brian Portnoy and Josh Brown wrote one of the better investing and personal finance books out there called How I Invest My Money. The TLDR is that most investment professionals spend years helping clients manage their portfolios with little discussion of what they do with their own money, and in each chapter of How I Invest My Money, a different investor shares the reasons behind their own investment processes. I was asked to write a chapter in the new edition coming out next year, and I spent the back half of my working on it. Very excited about this.

In other book news, I got my edits back from my editor, so it’s back to my own book grind for a bit. Probably going to run back my Spring 2025 playbook of Friday-Sunday writing, writing, writing for the next month, though editing seems to be a bit easier than turning a blank page into 60,000 words.

We (Slow Ventures) are hosting a Creator CEO Summit in Los Angeles on September 18th to discuss how different entrepreneurs and operators are leveraging social media platforms to scale their businesses. Space is very limited with 70 spots reserved for different creators and operators, but if this is you, and you’re in the area, shoot me an email.

What I’m Interested In:

I had an interesting conversation with Carter Abdallah (total homie, introduced by mutual friends from Atlanta) about the Gen-Z nihilism and the issue of young men “opting out” of society today. For context, Carter is a software engineer at Nvidia, but he also has 400k+ followers on his socials and a lot of his content is focused on life advice for younger dudes. Young men are increasingly impatient with their careers and finances, rising costs of living are painful, no one is going out / having sex, etc. Meanwhile, the “gamification of everything” from sports betting to stock trading has made the temptation of “risking it all” on a roulette spin more compelling than playing a long game, for many. This, obviously, isn’t great, but I’m curious what the fix, if any, will be.

While I don’t envy my friends who went through the investment banking gauntlet out of undergrad or business school, I do think, if you’re doing anything remotely-related to finance or investing (such as VC!), it’s good to at least have some barebones Excel / financial modeling skills. As a result, in the name of “upskilling,” I’ve been digging through a couple of general modeling Wall Street Prep courses over the last week.

Snap’s commitment to dumping every ounce of operating cash flow, and then some, into stock-based compensation, should be studied.

What I’m Reading:

The Cal Newport article I mentioned earlier on fixed-block scheduling is a great read for anyone else who struggles with procrastination and context switching.

A relatedly-hilarious (but valid) blog post from a Stanford professor about using “useful” procrastination to get more done by gaslighting yourself, basically.

One of my favorite Twitter accounts is “Blueprintsmb.” He’s an anonymous account that has been documenting his journey of going from the hedge fund world to running a small manufacturing business. Anyway, he shares occasional “life advice anecdote” types of posts from conversations with young professionals in NYC, and this one was particularly good.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Me quietly working hard three hours a day crushing my enemies

I think humans are especially inefficient when trying to be efficient. A thing I think AI will illuminate more so than anything else.

On your "what you're interested in" section, you mention Gen-Z nihilism... I think connection is the fix. Genuine connection.