On Meaningless Careers

Some thoughts on the pointlessness of so many jobs.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

"No one wants to work."

"The great resignation."

"Everyone is quitting."

You've heard it, I've heard it, we've all heard it. And it certainly seems to be true, especially in the white-collar labor market that dominates our world today.

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, millions quit their jobs in droves. They sought to pursue the "more important things" in life. They refused to return to an office environment. Companies were forced to pay employees more and more to entice them to continue working.

So yeah, given the state of everything, you could say that no one wants to work.

But this is an oversimplified take. Maybe it is because I feel compelled to defend my fellow Gen-Zers and millennials (as a 25-year-old, I have no idea which group to call my own), but people do want to work.

In fact, people love work.

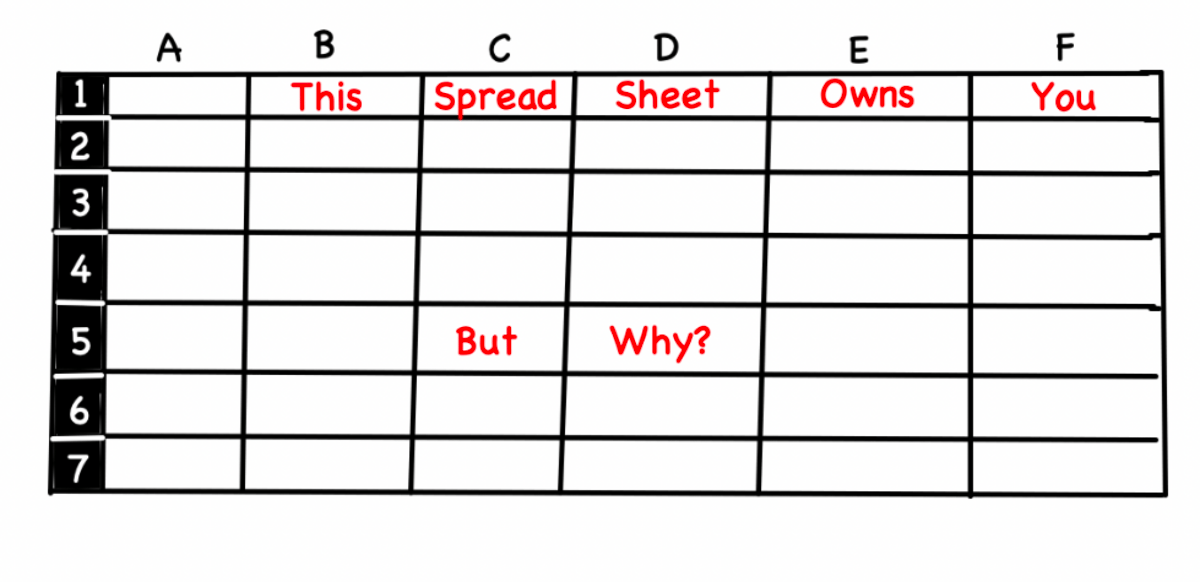

The problem isn't that the youngest generation hates work; the problem is that many of the jobs offered to the youngest generation aren't work at all. The spreadsheet-heavy, mid-level-manager-dominated, buzzword-filled roles offered to us are jobs, but they are hardly "work."

For any gamers out there, one of the oldest tricks in the book is giving your younger sibling an unplugged/disconnected controller, so they feel like they are "playing", while you are in control the whole time.

Many "jobs" today are simply unplugged controllers. The work would get done, whether or not we take part in the process. We are simply moving numbers, smashing buttons, and staying busy, with no regard for actual productivity.

We never stop to ask "is this job necessary?" Because we are paid increasingly higher and higher salaries for our participation in this ever-growing proliferation of pointless jobs.

Sebastian Junger once said, “Humans don’t mind hardship, in fact they thrive on it; what they mind is not feeling necessary. Modern society has perfected the art of making people not feel necessary.”

Everyone wants to work. In fact, most of us yearn for real work, but we have removed "work" from most jobs to our own detriment. We have replaced work with a glut of the unnecessary.

A Personal Anecdote

I played college football for five years, and college football, for the most part, sucks. Yes, playing ball on Saturdays is awesome. But game days, which are 4-hour events that occur ~12 times each fall, are 2% of the total college football experience.

The other 98%?

Dreading your 5:30 AM alarm every morning from ages 18-22, because at 6 AM you have to either lift weights, take an ice bath, or bash heads with other grown men while the rest of your classmates sleep for another four hours.

Putting on 20 pounds of equipment so you can spend two-hour practices colliding with 300-pound men in 95-degree heat.

Tearing labrums and wrist ligaments, suffering from concussions, and pulling muscles that you didn't even know you had, just to spend months rehabbing so you can do it all again.

Enduring two-hour film meetings where you are bombarded with alternating waves of praise and criticism based on your performance from that morning's practice or the previous week's game.

Forcing yourself to eat more (in some cases, a lot more) food to add and maintain an extra 25 pounds of body weight.

So yeah, football sucked. Anyone who played college football will tell you that it sucked.

And guess what else? I loved it. Most former players loved it. There was beauty in this struggle. A beauty in the "suck".

There was something special about a group of guys struggling towards a common goal, building something together, knowing that their individual efforts played an important role in the success or failure of the team.

When I was a scout-team player, I knew that my efforts in practice made our starters better. Beating a starter as a scout team player on Tuesday might prevent that same thing from happening in a game-time scenario that Saturday.

When I was a starter, I knew that the difference between victory and defeat could very well come down to me making a play in crunch time.

Football was overbearing, painful, and straight-up frustrating at times, but from day one on the football team, I felt like my contributions mattered.

Contrast that with my experience working in corporate finance.

The people I worked with and worked for in corporate finance were great. My supervisors were certainly nicer than my coaches (which wasn't a difficult hurdle to surpass, considering some of my football coaches called me things that cannot be repeated over text). And the work wasn't hard. It was easy, simple. And anything that I didn't already know how to do could be learned in a few days.

And the best part? I was paid a living wage for my efforts in this corporate finance job. And yet, I hated it. Actually, hate is much too strong of a word.

The opposite of love isn't hate, it's indifference. And I was aggressively indifferent to my work.

If pandemic-induced remote work showed me anything, it showed me how little "work" was necessary to do my job. I legitimately "worked" 5-10 hours per week at times, but I was always pretending to "work", by either moving my mouse to look active or tinkering with files, models, and decks that didn't really need tinkering to pass the time.

It was pretty obvious that if I didn't show up for a day, week, or month, the show would go on. I was playing with an unplugged remote.

I was trading my time for a paycheck, with no regard for the actual work being done.

And I wasn't alone. Plenty of my coworkers, as well as friends working for other companies, were all doing the exact same thing. One big facade of bullshit jobs.

Our Job Problem

For hundreds of years, there was a direct cause-and-effect relationship between your labor inputs and the resulting outputs. A farmer toiled in the field, and land would produce crops. A mechanic would fix machinery, a carpenter would build furniture, and a captain would navigate his ship.

But today? Today we have millions of high-paying jobs that rely on our abilities to manipulate numbers, send emails, and report to seven levels of superiors.

Bernie Madoff, Herbalife, and that wellness product that your high school classmates are shilling on Facebook have nothing on the pyramid scheme that is "Corporate America."

An idea that I increasingly believe is that half of all white-collar jobs could disappear tomorrow, and there would be no decline in productivity. In fact, productivity might increase.

We aren't working. Sure, we have jobs. We make money. Some of us make a lot of money. But these jobs are not work. They are distractions at best, and adult day-care at worst.

The Prestige Lie

The paradox of modern work is that the most prestigious jobs often involve the least actual work. If you can grind on tedious tasks longer than anyone else, you can get paid a lot of money. You gain material riches at the loss of your individualistic drive.

To quote David Graeber's Bullshit Jobs:

Shit jobs tend to be blue collar and pay by the hour, whereas bullshit jobs tend to be white collar and salaried. Those who work shit jobs tend to be the object of indignities; they not only work hard but also are held in low esteem for that very reason. But at least they know they're doing something useful.

Those who work bullshit jobs are often surrounded by honor and prestige; they are respected as professionals, well paid, and treated as high achievers - as the sort of people who can be justly proud of what they do.

Yet secretly they are aware that they have achieved nothing; they feel they have done nothing to earn the consumer toys with which they fill their lives; they feel it's all based on a lie - as, indeed, it is.

Of course, this whole thing makes sense. Prestige is the lie we tell ourselves to justify our "bullshit jobs."

We don't like the work, and in the back of our heads, it feels like we are selling our souls and our time for a paycheck. If we dwelled on that realization too long, we would probably hop off this treadmill entirely. But prestige is that North Star that continues to pull us forward.

The thing about prestige is that it isn't real. It's a vanity metric. Don't believe me? Then why are half of all middle-management jobs now called "vice president?"

Prestige.

Prestige has mollified our collective work restlessness, our existential angst. Prestige keeps those uncomfortable self-realizations imprisoned in the backs of our minds.

Prestige allows the show to go on.

But if you adjust your values, and if prestige loses its luster, the nothingness of these jobs becomes impossible to ignore.

So I implore you, whoever you are, to think about your own "job" this morning. Is your job fulfilling? Is it satisfying? Are you the director of your own life? Or are you simply playing the role that so many of us have played? Doing your part to keep the machine chugging along?

Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

Staying on theme, check out David Graeber's "Bullshit Jobs" on Amazon.

Also, The Atlantic's Derek Thompson wrote a super interesting piece on why rent inflation is insane.

There's something I think about a lot that you briefly touched on. When large swathes of people have seemingly unproductive jobs, how does anything even get done? Farmers and other manual laborers have to pick up the slack to support these people with food and other goods, because otherwise nothing of any real value is produced. Yet jobs that arguably contribute more to society are paid less.

It's really a tragedy and a complete failure of our economic system.

Bullshit Jobs was one of the most depressing books I ever read. It was too relevant to my career at the time.