Madness of the Crowds

How we conform to those around us.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

Let's Dance

Information about the following story comes from PDR.

In July 1518 in Strasbourg, France, there was a viral outbreak of sorts. This outbreak wasn't the black death that plagued Europe in the mid-1300s. It was an outbreak of dancing.

One mid-summer day, a woman named Frau Troffea took to the streets and began dancing. She didn't dance in a rhythmic, organized fashion, but instead twisted her body violently to a song that no one else could hear.

Within a week, dozens of others had joined Troffea in the streets, erratically dancing to their own silent beats. The city leaders grew concerned as the number of afflicted grew, and physicians recommended that the dancers must dance their condition away.

A stage was constructed, and musicians were brought in to help the sick purge their bodies of this illness. Yet the condition continued to spread.

By August, the crowd had swelled to an army of 400 dancers. Their feet began to bloody, their eyes glazed over, and a few even fainted and died after weeks and weeks of incessant dancing.

Finally in September, this mysterious affliction disappeared as quickly as it had appeared.

Smithsonian

At least ten examples of this "dancing fever" occurred throughout Europe in the Middle Ages, with the Strasbourg incident being the best recorded. All sorts of causes have been proposed:

Perhaps the infected had consumed some sort of fungi or hallucinogen that caused them to see and hear things that weren't there.

Maybe it was a curse from God or one of the saints. This condition was later referred to as "St. Vitus' Dance", named after the patron saint of dance.

But the prevailing theory is that these dancing plagues were simply madness of the crowds. The dancers worked themselves into a frenzy as their numbers grew.

Groupthink

The impact of others' actions on our decisions is a well-documented phenomenon. Take the elevator experiment as an example. Under normal conditions, you would never turn to face the rear of an elevator. However, when a group of "actors" already in the elevator are facing backwards, many new entrants will copy the group's actions to avoid standing out.

The Asch conformity experiments showed a similar effect. Eight male college students were told that they would be conducting a simple "perceptual" study. In reality, seven were actors, and the real study was on the response of the eighth.

All eight participants were given two cards with lines on them: one line on the left card and three on the right. All participants would be asked to match which line, A,B, or C, on card two matched the line on card one. They answered one by one, with the test subject always going last.

The actors would all say the correct answer for multiple rounds, before unanimously saying an erroneous choice in the following round. Each subsequent round after this, the actors' decision to choose right and wrong answer would vary, but they were always in agreement.

In 37% of instances, the test subjects would follow the crowd with the wrong answer, even though the correct answer was obvious.

We are social creatures that want to be accepted in our communities, and this desire to be accepted often leads to us (either subconsciously or intentionally) making illogical decisions for the sake of fitting in.

The madness of crowds.

This madness of crowds occurs in all areas of our lives: from dancing hysteria in medieval France, to social experiments, to financial markets.

Apes Together Strong

AMC Theaters.

A relic of years gone-by. A brick-and-mortar theater chain in an era of Netflix and Disney+. A company that, for all intents-and-purposes, should have bitten the dust when the pandemic shut down in-person activities for more than a year.

AMC's revenue, even after recovering from the peak of lockdowns, is still dismally below its average levels from the last decade.

Macrotrends

And yet, this same AMC, a left-for-dead movie theater chain, is worth 150% more than it was five years ago.

How?

Because AMC has become a point of cultural zeitgeist, the supposed-cornerstone in a struggle between the average Joes and Wall Street's finest. AMC fervor has grown so hot that the AMC stock subreddit page has half-a-million members.

Traders are willingly throwing tens, and even hundreds, of thousands of dollars down the drain to "invest" in AMC despite there being no rational thesis for the stock to go up.

Welcome to the madness of crowds, financial markets edition.

The Birth of the Meme Stock

GameStop, another struggling retailer, underwent the short squeeze of a lifetime back in January 2021. More than 100% of its shares were sold short, and a series of catalysts (Michael Burry taking a long position, Microsoft partnership, and Ryan Cohen's activist stake), caused the stock price to climb.

As short sellers rushed to cover their positions, the stock went nuclear, briefly hitting $500 per share. Exchanges couldn't handle the trading volume, and many restricted the buying of these "meme" stocks. The method by which trades are settled with clearinghouses was the catalyst behind the trading restrictions.

Without getting too complicated, stocks are settled using something called the T+2 method, meaning that trades are processed two days after the orders go through (hence, Time + 2). While it looks like the stock is instantly in your portfolio, in reality you have an accounts receivable of sorts.

Typically this doesn't cause issues... unless the same shares of a particular stock are trading 5x over each day, and the exchange has to have enough capital to cover all of the shares for each trade. This very thing happened to GameStop last January.

GameStop revealed cracks in this system, and volume had to be slowed.

But that wasn't the story that caught fire, because it wasn't exciting.

Robinhood, the exchange caught in the middle of this fiasco, is able to offer free trading because it sells its order flow to market makers, such as Citadel Securities. These market makers scalp pennies on each trade's bid-ask spread. Whether that's right or wrong is for you to decide.

A certain prominent hedge fund, Melvin Capital, was down billions after the short squeeze, because they had a massive GME short position. Melvin's CEO, Gabe Plotkin, was a former protégé of Citadel's CEO, Ken Griffin.

Griffin's Citadel invested $2B in Melvin Capital after the fund almost blew up.

The media and retail traders tied all of the information together, and came to the conclusion that Melvin, Citadel, and Robinhood must have been in bed together, and Citadel influenced Robinhood to suspend trading to bail Melvin Capital out.

Ironically, Citadel was making a killing on the short squeeze thanks to their payment-for-order-flow.

Now I'm going to draw a painfully oversimplified picture to demonstrate this weird love triangle:

Regardless of what you think GME's "fair value" was, trading was halted because the exchanges were going to implode due to the T+2 requirement.

But that story isn't nearly as juicy as the three-headed conspiracy, so the more popular narrative became Citadel pressured Robinhood to end trading. This ignores the fact that Citadel was making a ton of money on GME order flow, and they benefited from trading not being halted.

The general consensus after the GME saga was that Robinhood was in bed with short sellers, and they suspended buy orders to give these short sellers a chance to close their positions.

Now let's talk about sweet, sweet AMC.

Apes Together Strong

AMC's short interest at this same time was around 60%. This is certainly high enough to induce a short squeeze, but nothing like GameStop's absurd 100%+ levels.

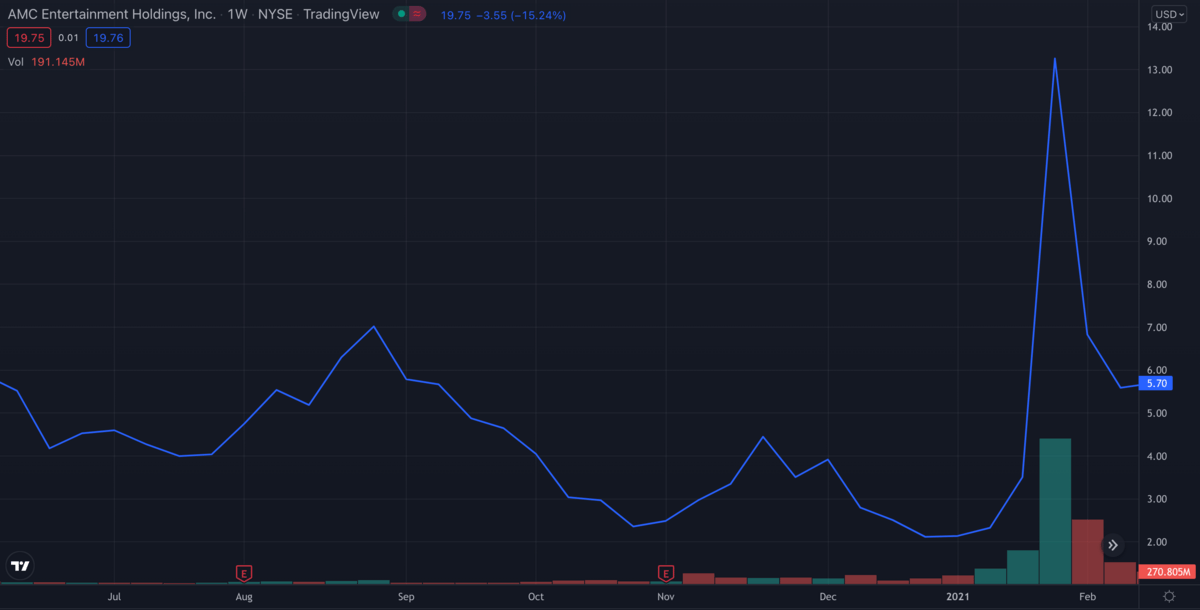

After GameStop took off, traders looked to other "meme stocks" (read as: dumpster fire companies that were similar to GameStop in every way minus the >100% short interest) to pump. Blackberry and Bed Bath & Beyond both ran 100%+, but AMC became the strongest sympathy pump.

While GME melted up to $400+, AMC had a decent run of its own. The theater stock climbed from $2 to $11, making a pretty penny for savvy traders.

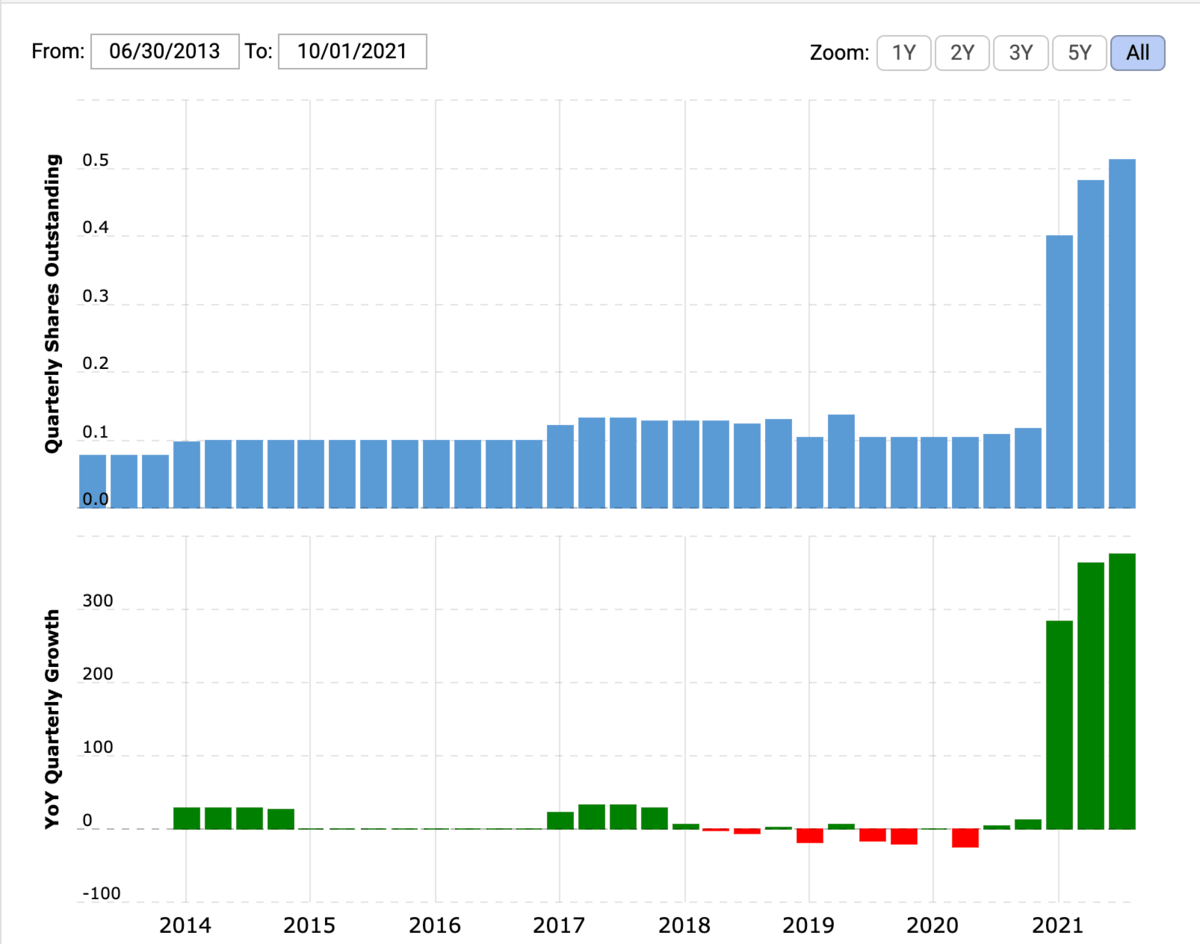

It also provided a great opportunity for management of the distressed theater chain to raise new equity by dumping hundreds of millions of shares on the market.

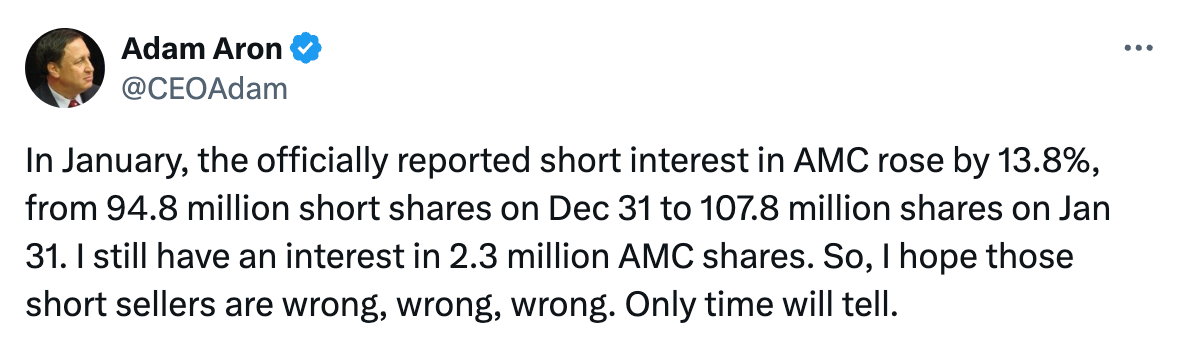

Now I don't fault management. In fact, this was a fantastic response by CEO Adam Aron: if retail traders want to pump your stock for no reason other than because they can, you take the layup and save your company.

And yes, this meme stock pump-turned-equity raise did, in all likelihood, save AMC.

By the end of January, the short squeeze is over, GameStop's prices come back down to earth, short sellers are licking their wounds, and all is right in the world... right?

LOL.

The short squeeze thesis surrounding GME originated months before the meme-pump, and the thesis was valid. GME was $10 a share, and it eventually broke through $400. That was, by definition, a short squeeze.

Despite GME climbing 4000% in a month, some traders were saying that the "squeeze had not yet squoze," and the real moonshot was waiting to come. Because 4000% is, of course, not much of a squeeze according to these guys. Robinhood had obviously bailed out the evil hedge funds, and they were net-short again. If everyone just held their shares, kept buying, and refused to sell, it would rocket to the moon again.

"We could get our revenge on the malicious hedge funds!"

This was no longer about making money, it was about sending a message.

Sure enough, just a month after GME's initial squeeze, traders again pumped it several hundred percent. And quietly, a certain movie theater chain continued to be bid up.

Then in May, seemingly out of nowhere, AMC went nuclear, climbing 500% higher than it had back it January.

Was AMC highly shorted at this point? No. Not only that, but the tradable float was 4x higher than it was in January, because the company issued millions of new shares. There was no logical thesis for an AMC short squeeze at this point. In fact, there wasn't a logical thesis of any sort for AMC to pump.

But stories, in the short-term, tend to overpower fundamentals. And the most absurd stories can create the most fervent followings.

Rumors ran amuck. Conspiracy theories about institutional investors using "synthetic shorts" to illegally suppress price movement spread across the internet. These bad actors were scared of the collective effort of retail traders, knowing that if they bought and simply refused to sell, AMC could hit $100,000 per share (giving it a market cap larger than the US's GDP. Seems legit).

Videos claiming $100, $1,000, and $1,000,000 AMC price targets emerged across TikTok, Youtube, and Instagram, with influencers pleading for their followers to "buy the dip." The AMC cult branded themselves as "AMC Apes", saying, "Apes together strong." CEO Adam Aron became the king Silverback, and he fully leaned into the attention.

Why not? The longer that the price stayed elevated, the more stock that he could dump on his beloved apes for millions.

Retail traders had worked themselves into echo chamber-induced frenzies, and like the afflicted peasants of Strasbourg that couldn't help but dance, these investors could do nothing but buy.

Like a game of telephone where the end message no longer resembles its origin, a well-constructed GameStop short-squeeze thesis had evolved into a nonsensical cult following of AMC, completely detached from reality.

A quick aside: While visiting Krakow, Poland last September, I met a guy in my hostel who had $100k, or 95% of his net worth, in AMC stock because he legitimately thought it was going to hit a minimum of $1,000 per share. AMC was at $47 around that time. I hope he's doing well.

A Distorted Reality

Let's look at the "story" of AMC, vs. reality.

Perception:

Greedy, evil hedge funds were manipulating market conditions by taking on billion dollar "synthetic short" positions in AMC stock. They were bailed out by their puppet broker, Robinhood, and it was the moral duty of collective retail traders to exact revenge. This was no longer about making money, it was sending a message.

Given the complex trade dynamics that no bull could concisely articulate, AMC's fair value was obviously $100,000 per share, giving the stock a higher theoretical market capitalization ($52T) than the GDP of America ($20T). This message was graciously shared across all social media avenues by disciples of the church of AMC. Anyone who didn't believe in the AMC bull case was simply failing to see the big picture.

AMC's fearless leader, Adam Aron, was the knight in shining armor that would lead his shareholders to the short-squeeze Valhalla. Buying AMC shares was a moral imperative.

Reality:

A failing movie theater got thrown a lifeline when day traders pumped the stock in response to a GameStop short squeeze. Management wisely used the opportunity to raise equity, likely saving the company. The same stock pumped even higher for a second time, as bits and pieces of the original GME thesis were spun into a tale of "synthetic shorts," institutional evil, and a call to action for investors to make the moral decision to invest in AMC. With cultish believers calling on others to "buy and never sell," AMC functionally became a pyramid scheme.

AMC's management fed the flames to pump the stock, while dumping millions of shares in the process. While they believed that they were "fighting the 1%," the self-proclaimed AMC apes simply padded Adam Aron's pockets at their own expense.

With the float now increased by 3x from share issuances and no further catalysts, the stock has slowly dwindled back down to a more reasonable level.

How the turntables.

A woman feverishly dances in the streets of Strasbourg, to the amusement of many. After a week passes, more and more join her. One month later, 400 strong are violently thrashing their bodies about.

To the detriment of their physical health, they danced til they bled. They danced til they fainted. They danced til they died.

All they could do was dance.

An investor believes that AMC is being manipulated by shadowy forces, and decides to invest hundreds of thousands and share his message with the world. After a few days, more join him. Suddenly, $AMC is trending on Twitter and Reddit, and thousands feel compelled to join this fight against evil.

To the detriment of their financial health, they held through share issuances, they held through insider sales, and they held as the stock slowly drifted down to zero.

All they could do was hodl.

Rationality is subjective, largely dependent on the communities that we surround ourselves with. To a random observer, it seems absurd that someone would invest their savings in a movie theater chain that is worth 10x what it was just two years ago.

At the same time, to one of the 500,000 members of the AMC subreddit who constantly absorbs information about price suppression, short squeezes, and manipulation, the most rational decision is investing one's savings in a movie theater chain that is worth 10x what it was just two years ago.

We are only as rational as the communities that we surround ourselves with, so we must be careful not to get caught up in the madness of our own crowds.

Happy Monday, let's dance.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!