Life Pro Tip: Learn to Write

A skill that everyone can take advantage of, but few ever do.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

Writing is a paradox. Stuff that is difficult to read is easy to write, while stuff that is easy to read is excruciating to write. Everyone knows how to write sentences. Few are able to craft stories. Great writing uses simple words to describe complex concepts. Terrible writing uses complex words to describe simple concepts (hello 99% of academia and finance literature).

My favorite paradox? Writing can benefit everyone, regardless of their chosen career path. But few take the time to develop this skill. Why should you want to become a better writer? Let’s dive in.

What You Know vs. What You Think You Know

Our minds are an ever-moving, jumbled maze of information. Imagine a Google Chrome window with 200 open tabs, where you are constantly jumping from tab to tab. That’s your brain.

While working on a project in your office, you will start thinking about your dinner plans. And your fantasy football lineup. And Elon Musk’s latest tweet. And a million other things. It’s pretty cool that our brains can handle so much information at once. Truly the world’s greatest supercomputers.

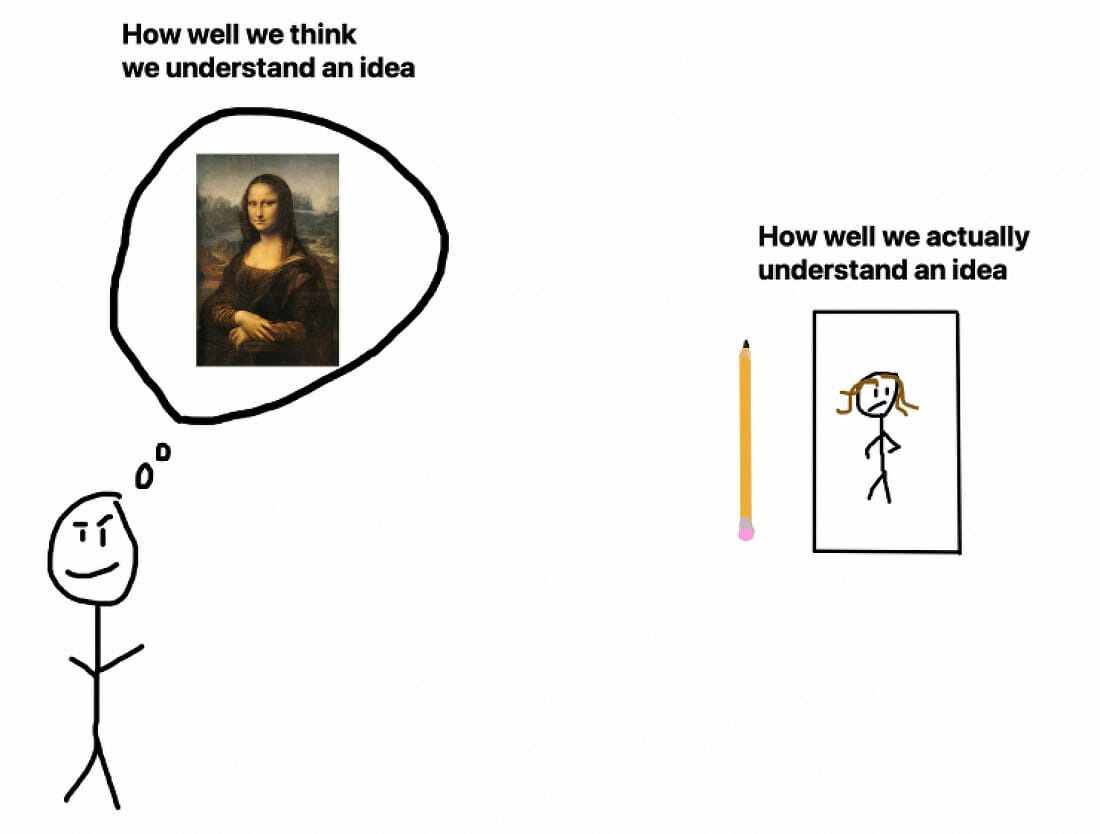

However, there is a drawback to the brain’s processing power: it is really, really hard to cultivate a deep understanding of pretty much anything. Our brains optimize for inch-deep, mile-wide thoughts, but the opposite is more important. To illustrate this, I’m going to ask you a ridiculously divisive question that would most definitely kill a first date:

What do you think of Joe Biden’s presidency so far?

Oh yeah, we’re going for the jugular this fine Wednesday morning.

Depending on your social group, where you live, and the media that you consume, you probably think one of three things:

He’s the worst president in history

He’s done a great job of leading our country through a turbulent period

He hasn’t really done anything (good or bad) of note

Put simply: bad, good, or neutral. And you are probably pretty confident in your belief.

Now a follow up question:

Can you write a detailed record of how specific events from his presidency have helped you form these beliefs?

Well that’s a little bit harder. Everyone has their initial thoughts about President Biden’s performance. And we assume these thoughts are fully-formed, because they make sense during the fleeting moments that they occupy our minds.

Now try writing “why’s” to explain the “what’s”. That’s a difficult task. Here’s what this process looks like:

Politics are a glaring example of this information disconnect, but it is a universal concept. Some other things that you know, but you probably don’t know.

What drives investor behavior in markets?

What do you look for in the ideal partner?

What do you want to do with your career?

The list goes on and on. Writing is both incredible and incredibly frustrating, because only by putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) can you realize just how little you know about something. Which in turn is the best way to learn more about that thing.

Problem Solving

You don’t know what you don’t know about a subject until you try to write about what you think you do know. And when you try to write about what you think you do know, you’ll likely have a few revelations:

I don’t know if this thing is true

I don’t know why I feel a certain way about that thing

I only have a surface level understanding of this other thing

I can’t find the words to tie my incongruent thoughts about all of these things together

Before setting out to write about the subject at hand, you thought you understood the full picture. As you open the Word doc, you realize that all you have are some connected edge pieces, and the final picture is unclear. And then you come to a glaring realization:

If you can’t write about it, you don’t understand it.

Imagine you have a 1,000 red, orange, and brown puzzle pieces scattered across the ground, and no box to use for reference. You might think the pieces will come together to form a beautiful brick house.

Yet as you put together your puzzle, an entirely different picture begins taking shape. Instead of red brick walls, the pieces slowly transform into vibrant leaves. Your house wasn’t a house, it was a beautiful forest in autumn.

And that’s how the writing process works. As you dig deeper and deeper into your research, your preconceived notions are often replaced by something entirely knew.

Writing helps you solve problems, because it forces you to figure things out in order to make your writing make sense. These solutions may mirror your original ideas, or they may take an entirely new form.

You won’t know what your final product will look like until you start writing, so you need to get started.

Your Memory Ain’t That Reliable

What did you eat for lunch last Wednesday?

You probably have no idea, right?

If you can’t remember something as simple as your meal from a week ago, do you really think you’ll remember your goals from five years ago? Your former attempts to solve a problem at work? Your biggest worries from early in your career?

Not a chance.

Memories lie, records don’t.

Your written word is a timestamp of your thought process at a given point in time. When new challenges arise, you can see how you handled similar situations in the past. In an era where the goal post won’t stop moving, your old writings allow you to see just how far you’ve come. While your career aspirations might change like the weather, your old writings show you what you wanted, and why you wanted it.

Your previous writings can give you all sorts of useful insights.

But your memories? All they can provide you with is a distorted view of how you think that you thought in the past.

Writing Scales

There are two skills that scale better than anything else: coding and writing. One piece of work can be used or consumed by millions. If you’re reading this, you probably don’t know how to code. That’s okay, because if you’re reading this, you most definitely know how to write (the ability to read and the ability to write go hand in hand, you know).

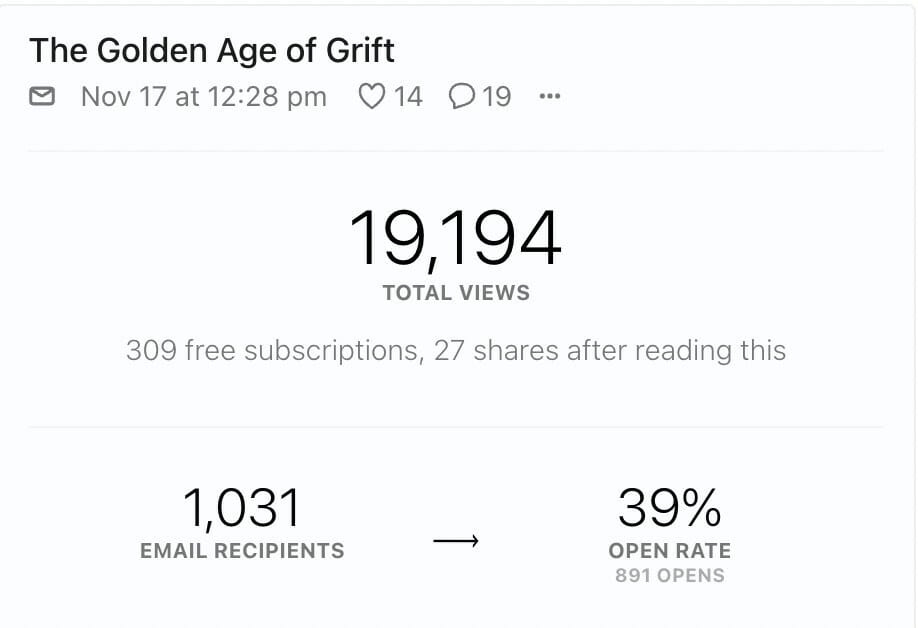

Last month, I wrote a piece called The Golden Age of Grift. I sent this piece to 1,031 subscribers. It was read more than 19,000 times, and it drove 309 new subscribers.

Why? Because a bunch of people on my email list read it. And a bunch of my Twitter followers read it. And they shared it with their networks. And some people in those networks shared it with their networks. And before I knew it, a lot of people had read something that I wrote.

Writing is the best tool for most people to gain the most exposure. Thanks to the internet, anything that you write can be instantly shared with the world. And if the world likes it?

The world will share it as well.

Most People Suck at Writing

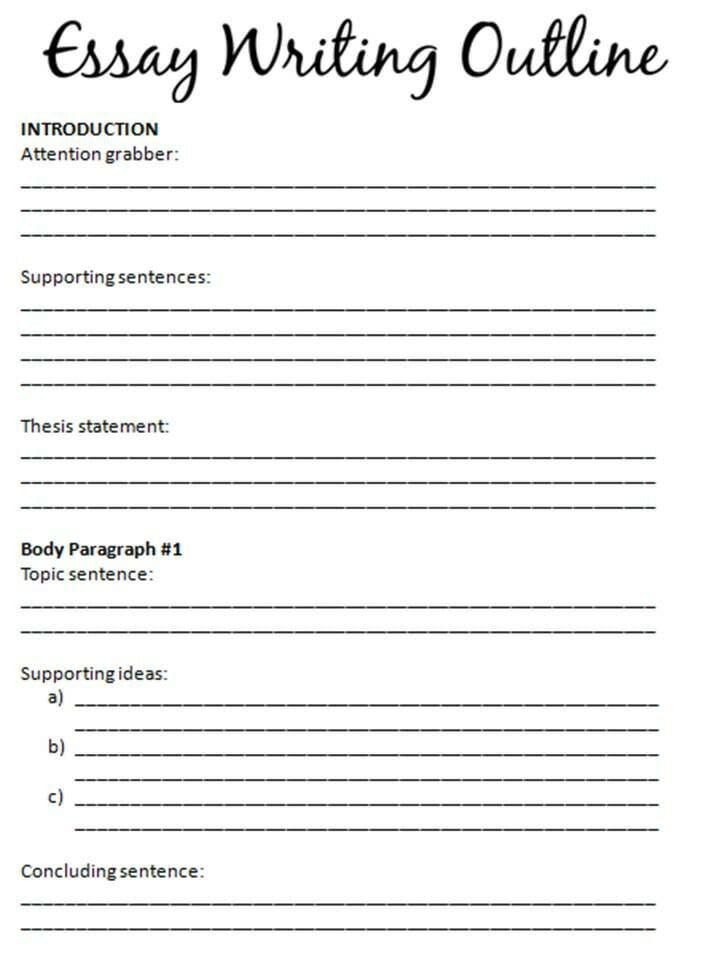

Most of us were never really taught how to write. I’m 99% sure everyone learned the same generic writing template when they were 12. To prove my point, I googled “how to write basic essay middle school” and found this gem:

Look familiar? This, ladies and gentlemen, is the first (and often only) writing framework taught to hundreds of millions of Americans. It’s like the y=mx+b of literature.

Just create one bold statement, 3 sentences to back that statement, and then basically repeat that first statement with a new statement. And do that over and over again until your paper is done.

Whoever came up with this framework should be thrown in the writing Gulag. There is nothing, nothing, worse than reading six-sentence paragraph after six-sentence paragraph of a cookie cutter essay in this format. But that is how we learn to write.

This model carries us through middle school, then high school, then college. And our vocabularies evolve, but writing style stays static. So we have the same paragraphs with the same structures, but bigger and bigger words.

A lot of people lean into the idea of using bigger and bigger words. After all, using an elaborate vocabulary to describe simple concepts probably makes you look smart. But good writing isn’t supposed to make the writer look smart. This is actually counterproductive, because it runs the risk of making your reader feel dumb.

Good writing uses simple language to explain complex ideas. But the best writing? The best writing uses engaging stories to connect with readers. Which leads to my final point.

Story Telling Is a Superpower

If a tree falls in the middle of the forest and no one is there to hear it, did it make a sound? If you have a skill or idea that you can’t effectively communicate to others, does it matter?

Same energy.

I previously wrote about the importance of having a good story.

Being able to tell your story is an advantage, as you can put the why behind all of your whats. But telling your story is a linear action. You talk to a recruiter. Or admissions committee member. Or company director.

1 on 1.

1 on 1.

1 on 1.

You tell your story well, but it spreads slowly by word of mouth alone. Writing your story? That is an exponential action, because anyone can see it. I literally wrote a story about myself last week:

More than 3,000 people read “my story”. But your story doesn’t have to be a 4,000 word article about you. It could be the story of the business that you built. The challenge that you overcame. The skill that you have. And anyone in the world could read it.

Telling your story will help you impress the person on the other side of the desk. Writing your story will help you impress billions on the other side of the screen.

Stories are leverage for your skills. Writing is leverage for your stories.

Better Writing = More Money

The best part about writing? If you’re good, you can get paid.

You can build an audience (which can be monetized through advertisements or paid subscribers). People may also pay you to write for them (which is another form of monetization).

But it’s not just “writers” who benefit financially from good writing. It’s everyone.

Good writing can translate into new job opportunities when someone comes across your work. Or increase your chance of landing an interview when you eloquently explain why you are a great fit for the role. Or make you a stronger graduate school applicant when you vividly recall how you overcame adversity.

All of which will (hopefully) help you make more money.

So how do you get started?

Go write some stuff that sucks. And then write some more stuff that sucks less. If you do it long enough, you’ll write decent stuff, and you can reap the rewards of decent writing. Good luck to all.

-Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!