Instacart's IPO and the Problem with "Series I's"

Private funding rounds forever was never a good idea.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

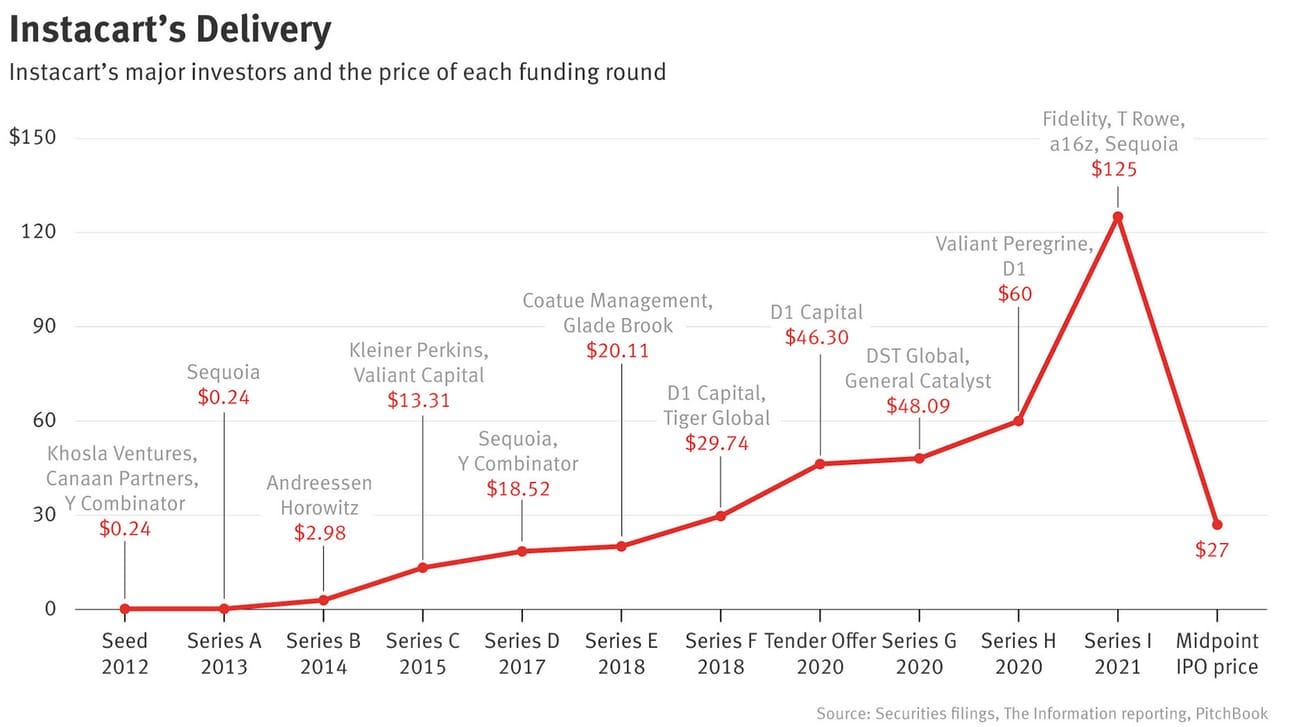

Today, venture-funded grocery delivery startup Instacart will hit the public markets at an estimated ~$30 per share for a $10B fully-diluted valuation. Under normal circumstances, a venture-funded startup hitting the public markets at a $10B valuation is a grand slam for everyone involved.

But Instacart’s IPO isn’t occurring under normal circumstances, and for many investors, it is more of a strikeout than a grand slam:

What happened?

In March 2021, when Covid was raging and grocery delivery services were the only thing separating us from societal collapse, Instacart managed to raise a $265M Series I at a $39B valuation.

But in 2023, after the Fed hiked interest rates at the fastest pace in history, tech valuations imploded, and grocery delivery services were once again viewed as “luxuries” and not “necessities,” a $39B valuation didn’t make a ton of sense, and investors waiting for their big exits will likely receive 25% refunds.

Instacart isn’t alone in its valuation drawdown. While they elected to hit the public markets, fellow startups Stripe, Klarna, and Ramp, which previously raised capital at $95B, $45.6B, and $8.1B valuations respectively, have all recently closed new funding rounds at $50B, $6.5B, and $5.5B valuations.

How did we reach the point that all of these “unicorn” startups are now experiencing such insane declines? To answer that question, we should turn the clock back to 2009.

The easiest path to “wealth” in the 13-year period between ~2009 and ~2022 was joining and/or investing in the right early-stage startup.

The reason? You could get rich without that startup ever figuring out how to make money, because as long as the company was “growing” (defined as revenue going up, regardless of profit margins), someone else would pay more money to invest at a higher valuation. The cycle went something like this:

Startup raises venture funding

Startup scales revenue rapidly (ignoring profitability)

Startup uses its high revenue growth rate as justification for more funding at a higher valuation

New investors invest more capital at a higher valuation

Repeat steps 2 through 5

What happened when the startup’s valuation increased? The value of shares owned by founders, early employees, and investors increased as well. Everyone got paid, and everyone was happy.

The problem was that none of this “wealth” was liquid. Paper net worth is cool, but if no one is willing and able to buy your stake, it’s not really worth all that much.

Imagine, for example, that I decide to raise venture capital for Young Money. I let you take a 0.00001% stake in Young Money for $10, while I retain 99.99999% of the company.

Technically, after raising this capital, I now own a $99,999,990 stake in Young Money, making me quite rich on paper. But in reality, no one is going to pay me $99,999,990 for the other 99.99999% of my company, so it’s not functionally worth anything near that much.

While this example is an exaggeration, it’s not all that far off from what’s been happening in venture capital over the last decade: cycle after cycle of startups raising more money at higher valuations, but in many cases, no one ever sold.

This wasn’t how the venture capital model was designed to function.

Traditionally, startups might raise some venture money to fund them until they reach profitability. At this point, they could either A) go public or B) be acquired by a larger firm. In either instance, the early investors would be well-compensated for their investments. But since ~2009, startups haven’t really had to be profitable, because someone was always willing to invest more money if they continued to grow.

And things really got out of hand when the Fed cut interest rates to zero.

In January 2023, I wrote a somewhat satirical piece listing 11 things caused by 0% interest rates. One of the culprits? A venture capital-subsidized lifestyle. To quote myself:

Let's turn back the clock to May 2020. You, me, and everyone else are stuck working from our apartments all day every day. Your pantry is running low, but instead of rewearing that disgusting cloth mask for the 27th time as you browse the aisles of your local Kroger, you decide to use one of 27,234 different grocery delivery apps that gives you 50% off all purchases made that month.

Next month, you repeat the process with a different app or different email, and the cycle continues. Venture capitalists poured billions into finding the "Uber of groceries," (and there were a lot of Ubers of groceries) and we consumers benefited by literally getting free food hand-delivered to our apartments.

And this VC-subsidized service wasn't limited to grocery delivery services either! Ubers and Airbnbs used to be half the price of taxis and hotels, and you could whip a Bird scooter around Washington D.C. for $1.50. At some point, however, all of these companies either began charging more money (profitability does matter!) or they went bust.

Ironically, I wasn’t that far from the truth. Previously-high valuations seemed conservative now that treasuries weren’t providing any yield, and investors threw even more money at these same startups at valuations 2-3 higher than just a year earlier. The machine continued propelling itself.

This zero percent interest rate environment wasn’t going to last forever though, and some startups, sensing opportunity, filed for IPOs at the peak of the craze. Investors in companies like Robinhood, Coinbase, Unity, and Affirm made millions (and in some cases, billions) as they were able to sell their shares at the peak around 2021.

But other startups like Instacart that opted for yet another private funding round instead of IPOing are now paying a hefty price: massive haircuts across the board.

So where do we go from here?

My $0.02: the “Series I” is dead. If your company can’t reach profitability by the time its funding round name approaches the 10th letter of the alphabet, it shouldn’t continue to operate as a company. Profitability (finally) matters, and venture capital will no longer subsidize zombie companies with sub-par margins.

As a result, we will see more startups operate with leaner business models, and many will go public sooner. Private markets are warm and safe because companies are required to disclose far less financial data, and company executives are only beholden to a small number of investors, but public markets represent liquidity events and accountability.

RIP to the venture feedback loop of the last decade, it was fun while it lasted.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!