Indefinite Optimism

The problem with pursuing optionality at all costs.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

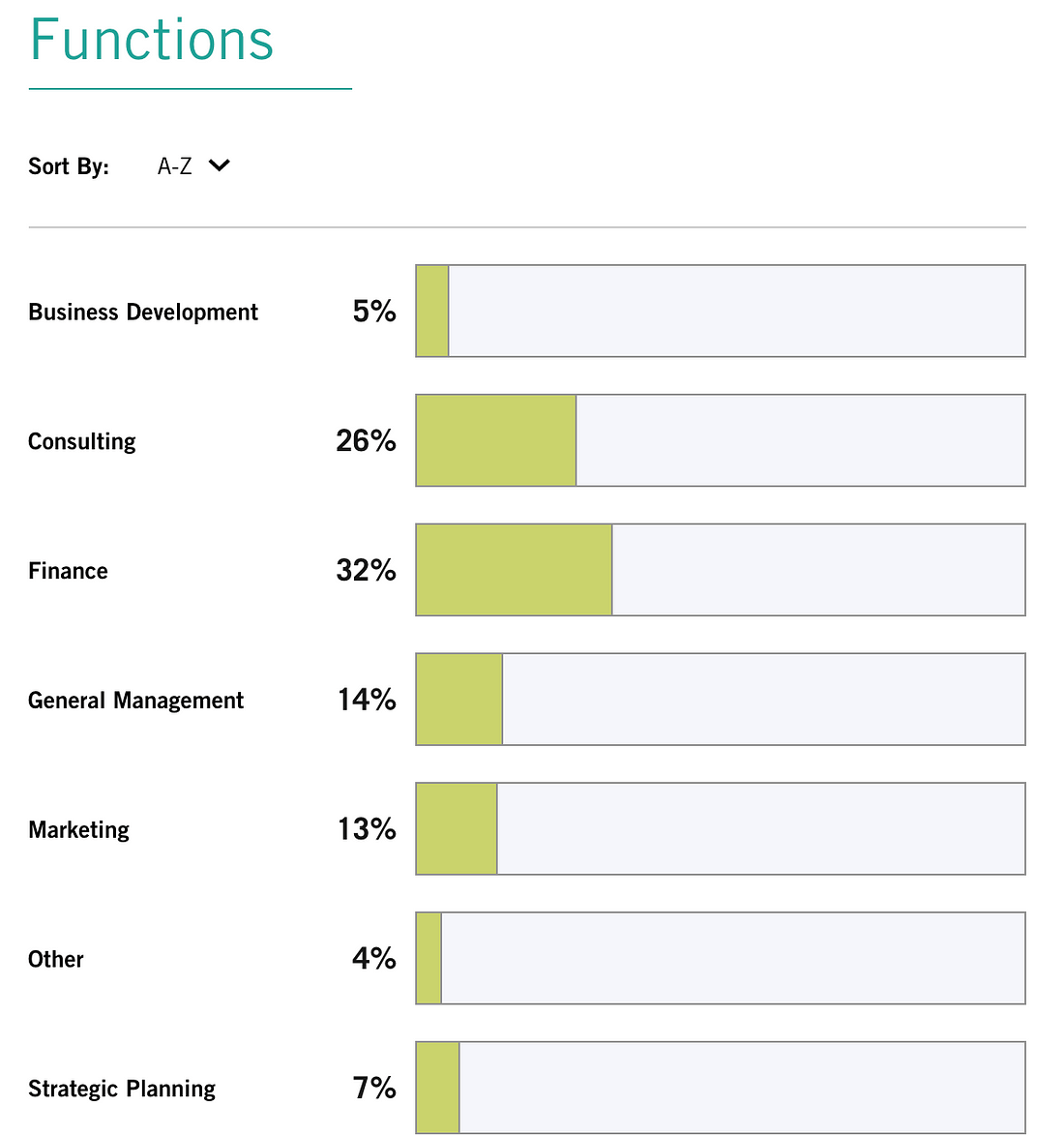

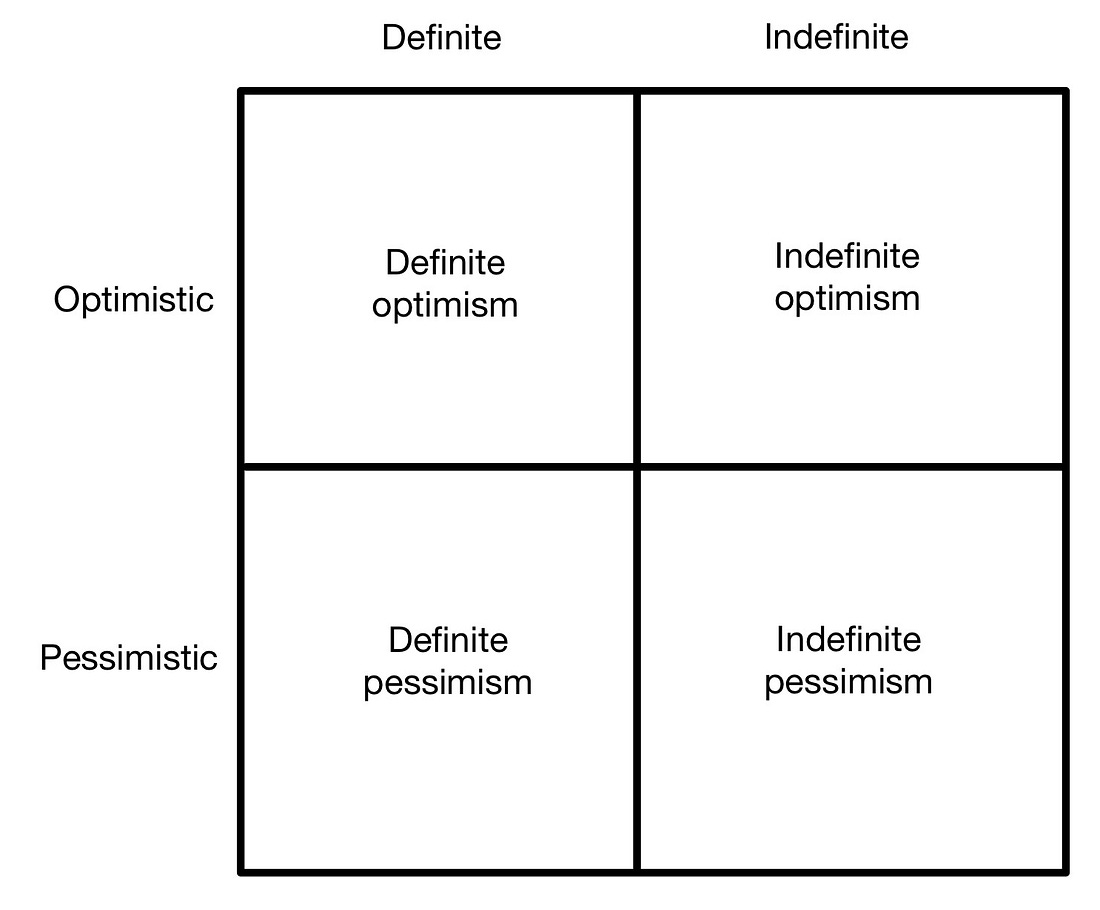

Peter Thiel is America’s most intriguing entrepreneur. A Stanford Law graduate, Thiel bucked the traditional legal career path to build PayPal with the “PayPal Mafia”. Besides founding two billion dollar companies, Thiel is also an avid investor and author. In his book Zero to One, Peter breaks down the world into a 2x2 matrix:

The definite optimist builds the positive future that he imagines

The definite pessimist prepares for a bleak future that he forecasts

The indefinite optimist assumes a positive future but has no plan for creating it

The indefinite pessimist thinks the world is going to shit, and has no idea what to do about it

I want to focus on point three: the indefinite optimist. Check out Thiel’s thoughts on indefinite optimism in America right now:

Indefinite optimism has dominated American thinking ever since 1982, when a long bull market began and finance eclipsed engineering as the way to approach the future. To an indefinite optimist, the future will be better, but he doesn’t know how exactly, so he won’t make any specific plans. He expects to profit from the future but sees no reason to design it concretely. Instead of working for years to build a new product, indefinite optimists rearrange already-invented ones. Bankers make money by rearranging the capital structures of already existing companies. Lawyers resolve disputes over old things or help other people structure their affairs. And private equity investors and management consultants don’t start new businesses; they squeeze extra efficiency from old ones with incessant procedural optimizations. It’s no surprise that these fields all attract disproportionate numbers of high-achieving Ivy League optionality chasers; what could be a more appropriate reward for two decades of résumé-building than a seemingly elite, process-oriented career that promises to “keep options open”?

How does indefinite optimism affect our careers, and what can we do about it?

A World Built on Indefinite Optimism

“To an indefinite optimist, the future will be better, but he doesn’t know how exactly, so he won’t make any specific plans.”

Modern day America is built on a roadmap of indefinite optimism. Beef up your resume to get into a good school. Repeat this step to get a good job. Repeat this step at said job to have optionality for new jobs. There’s no central thesis guiding your actions, but you’re confident that you’ll end up at the right place. It’s a 40 year game of “keeping your options open”, and riding the wave up.

Risk taking? Building things? Creating things? Breaking things? Failing, and failing again? We don’t do that here. We get a four year degree, to get a 40 hour job, to work our way up promotion after promotion. We use these promotions to boost that resume to move to another job. Why do we do that? Because it works. It’s worked for 50 years, so it’s bound to keep working for the next 50.

Indefinite optimism has convinced our best and brightest the they should spend less time building the future, and more time optimizing the present. What does that look like in practice? Entrepreneurship, engineering, and art have been replaced by finance, law, and consulting.

58% of Harvard Business School’s most recent graduating class accepted roles in consulting or finance.

Our most ambitious operators used to create new businesses, inventions, and expressions. Now they rearranging existing money, rules, and people. I don’t know how we came to the conclusion that peak capitalism is either moving money around to make more money, or moving people around to save more money. But here we are.

Indefinite Resumes

I played 44 days of Call of Duty, MW2 back in the day. There’s a term in CoD known as "“spray and pray”. Spray and pray involves unloading an entire clip at the other team, hoping some bullets would hit. It’s a scrub move. In the CoD realm, everyone knows that spray and pray is a trash strategy. In high school and college, it’s the premiere method for beefing up your resume.

“Get involved in extracurriculars,” said every high school guidance counselor. So you play football. And join the Spanish society. And volunteer with an animal shelter once a month. And write a few articles in the local paper.

You’re adequate at a dozen things, but a master of none. But college admissions often look for inch deep, mile wide resumes, so you get accepted.

In college, your career services rep tells you to get involved all over campus. So you help with a service project overseas. And join the investment club. And volunteer as a TA. And lead campus tours. And you get an internship one summer that looks good on a resume, even though you couldn’t care less about the work. Professional spray and pray.

You’re adequate at a dozen things, but a master of none.

Check out my resume from February 2019 (senior year of college).

Experience? Intern for a big company in my college town, intern for a Congressman, finance research, volunteer service project.

Skills? A bunch of things that I’m sort of good at, nothing that I dominate.

Activities? Football, fraternity, volunteer work, study abroad, club.

My resume was like every other college kid’s: a ton of stuff without much depth.

I was adequate at a dozen things, but a master of none.

Sure, I tentatively wanted to work in finance. Yeah, I made good grades and did a lot around campus. But at no point did I have a specific, concrete objective that I was working towards. How was I supposed to cater a resume towards a nonexistent goal? My resume is a textbook example of indefinite optimism.

But the indefinite optimist in us thinks that by doing a variety things in a condensed period of time, we’ll appeal to some recruiter, which will help us land some job. Maybe one point on my resume will stick, and I can leverage that to land a job.

Entering an Indefinite Job Market

When I graduated from college, I had no idea what I wanted to do for a career. Why would I? My goal for the last four years had been graduate college with a decent GPA and some internship experience. I had some hazy long-term plan to become CEO of a Fortune 500 company, but that was it. Real stimulating stuff there.

I wanted to do consulting because that sounded cool, and it would look good on a resume. But I wasn’t going to get a consulting gig at McKinsey, Bain, or BCG out of Mercer. So I applied to every finance job I could find. UPS, Norfolk Southern, Home Depot, etc. I landed the job with UPS, and my team was awesome.

But the whole time I was working at UPS, I knew it was a placeholder. Because I was going to go to Columbia Business School in a couple of years, and get a kick-ass degree. And go make bank working for McKinsey, Bain, or BCG. And after four years working there, I would pivot to a high-level gig with a client company.

And the circus continues. Sounds pretty hollow now, looking back.

Work culture within companies supports indefinite optimism as well.

“You can work in a variety of roles here. Gaining a variety of experiences will help you get a promotion down the road.” Note the implied goal here: work on all of these things so you’ll be more competitive at moving to the next stage. And then the process repeats at this stage. And so on.

What’s the point? Keep advancing to the next stage of the game as long as possible? Can anyone win a game that extends into perpetuity?

Playing an Indefinite Game

“Remaining flexible” in your dating life when you’re young and single sounds awesome. Not wanting to get tied down in your 20s, you keep your options open as long as possible. But if you wait too long, you’ll find yourself in your mid-30s with many of the good options already taken. You never took the time to cultivate a serious relationship, and now you’re scrambling to find someone to latch onto.

In relationships, the folly of perpetual optionality is obvious. In careers, it’s more discreet. You were a superstar student unsure of what to do after graduation, so you work for Goldman Sachs or McKinsey & Co. Why? Because they look good on a resume, and they’ll provide you with options for later. After two years, you get your MBA because it looks good on a resume, and it will let you move to private equity. And then you spend your tenure in private equity looking for something else, because that’s all you know. Do one thing to get to the next thing. And your career consists of jumping to a dozen things with no end goal.

There is nothing wrong with changing jobs or industries. On the contrary, I encourage trying an abundance of things. But flexibility as an end goal creates two glaring problems:

You never commit to any career or path, because you always have one foot out the door.

You are never satisfied with your work, because it was just another stepping stone to something else.

Optionality for optionality’s sake never accomplishes anything fulfilling, because everything you do is merely a prerequisite for something else. There’s no passion, no purpose, no struggle, and no real success.

Do you really want to “win” a game that you never enjoyed playing in the first place?

Defining Yourself in an Indefinite World

Do more by doing less.

Flexibility is overrated. Doing what you’re “supposed to do” is overrated. You want to stand out in a job market saturated with indefinite optimism? Define yourself. Spend less time ironing out your weaknesses, and more time doubling down on your strengths.

There are a million job candidates who are sort of good at dozen different things. People who had a 3.7+ GPA in finance, joined a couple of clubs in college, are proficient in Excel, and know their way around financial statements. When you’re another jack of all trades (pun 100% intended), the world is your competition.

But what if one candidate speaks four languages? Or starts their own business? Or publishes 100 articles online in six months?

What’s going to stand out? The guy who can run a linear regression and use VLookup, or the candidate who built a social media site for college athletes?

Find an area where you are talented or passionate, and lean into it. Spend less time racking up trivial resume points and Linkedin training courses, and more time cultivating a specific skillset.

You can spend five years pursuing a variety of skills, and you will end up being competent at many things, and an expert at none of them.

OR you can spend five years honing a specific craft, and you will end up being the best of the best in your niche.

Indefinite optimism is easy, because the playbook has already been created. Beef up the resume, get the job, get some new experiences, level up to the new job, rinse, repeat. But there are limits to getting my efficient at the current playbook. Indefinite optimism will only work as long as definite optimists continue to drive progress. The risk-takers who fail, fail, and fail again until they hit a breakthrough.

You want to stand out in a world of indefinite optimists?

Struggle with something. Fail at something. Be terrible at something. Then do it longer than everyone else. At some point, you’ll be better than most. If you stick at it long enough, you’ll be one of the best.

What do I want to do? Write. And write. And write some more. And take advantage of whatever opportunities come from writing. I’m not going to spend the next forty years saturating a resume with accolades that don’t matter to me.

Being the best at one thing > > > being mediocre at a dozen things. Find your thing, and go dominate.

Move from the top right to the top left.

Have a great weekend, amigos.

-Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!