Americans Aren't Poor, They're "Pre-Rich"

Some thoughts on the transitive property of American poverty.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

In the centuries leading up to the French Revolution, France operated under a three-estate system, known as the Ancien Régime, which divided the nation’s population into three groups:

Clergy, or First Estate

Nobles, or Second Estate

Peasants and bourgeoisie, or Third Estate

These estates were static: if you were born a peasant, you would grow up a peasant, and you would die a peasant. If you were fortunate enough to be born into the noble class, you would learn Latin, reside in your family’s manor or chateau, and break bread with other aristocrats from around the country. For most of human history, rigid systems such as the Ancien Régime were the status quo, and peasants only had two hopes for improving their social standing: disease and war.

In The Great Leveler, Austrian historian Walter Scheidel discussed how the Black Death and World War II reduced wealth inequality in Europe and Japan.

Black Death:

“Regardless of whether the plague actually killed more people of working age than it did those younger and older, as is sometimes maintained, land became more abundant relative to labor…

According to the Chronicle of the Priory of Rochester: such a shortage of labourers ensued that the humble turned up their noses at employment, and could scarcely be persuaded to serve the eminent for triple wages.”

World War II:

“The declared real value of the largest 1 percent of estates in Japan fell by 90% between 1936 and 1945 and by almost 97% between 1936 and 1949. The top 0.1% of all estates lost even more - 93% and more than 98%, respectively. In real terms, the amount of wealth required to count a household among the richest 0.01% (or one in 10,000) in 1949 would have put it in only the top 5% back in 1936.”

I guess mass death and societal collapse are excellent for class mobility, assuming you survived to benefit. However, these flattened class structures didn’t last forever. Within a few years, demographics recovered and wealth inequality was back on the menu.

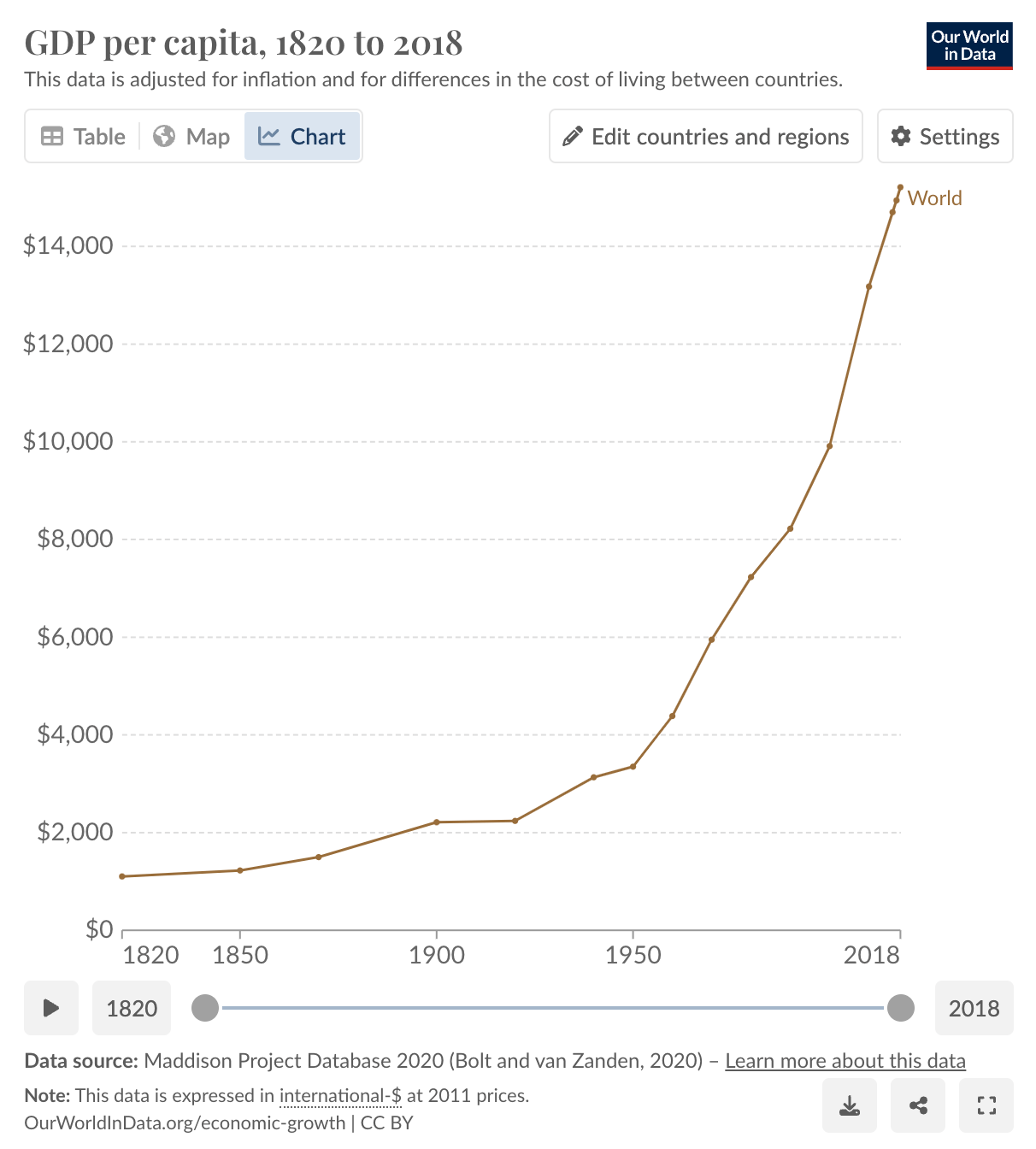

This cycle of static wealth hierarchy —> brief disruption —> static wealth hierarchy continued until the global industrialization and technological innovation that followed World War 2 led to an explosion in GDP per capita:

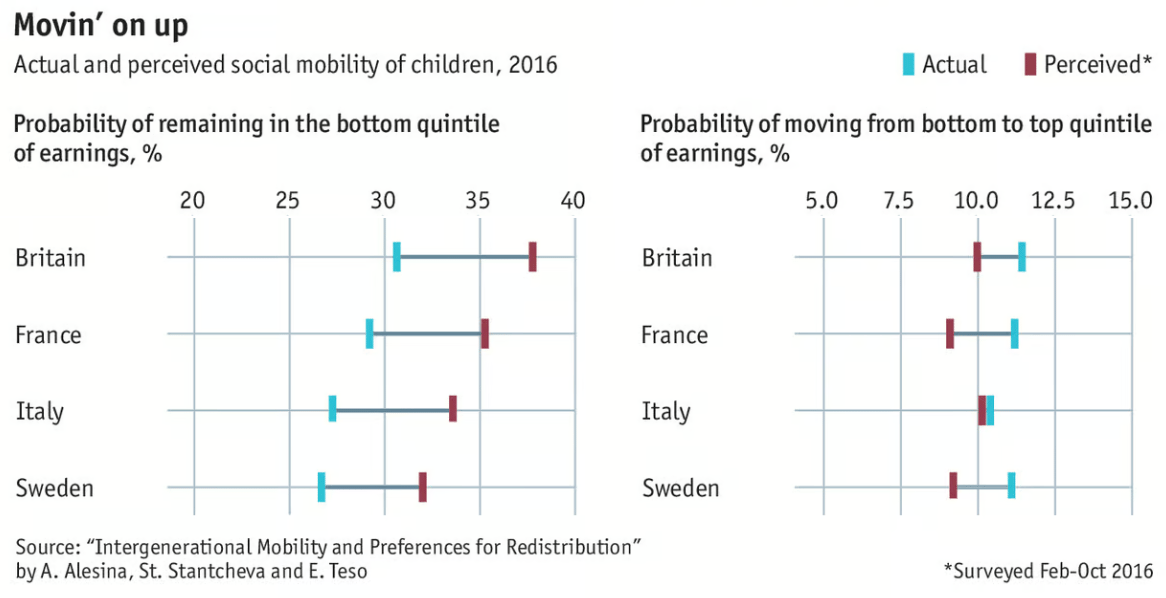

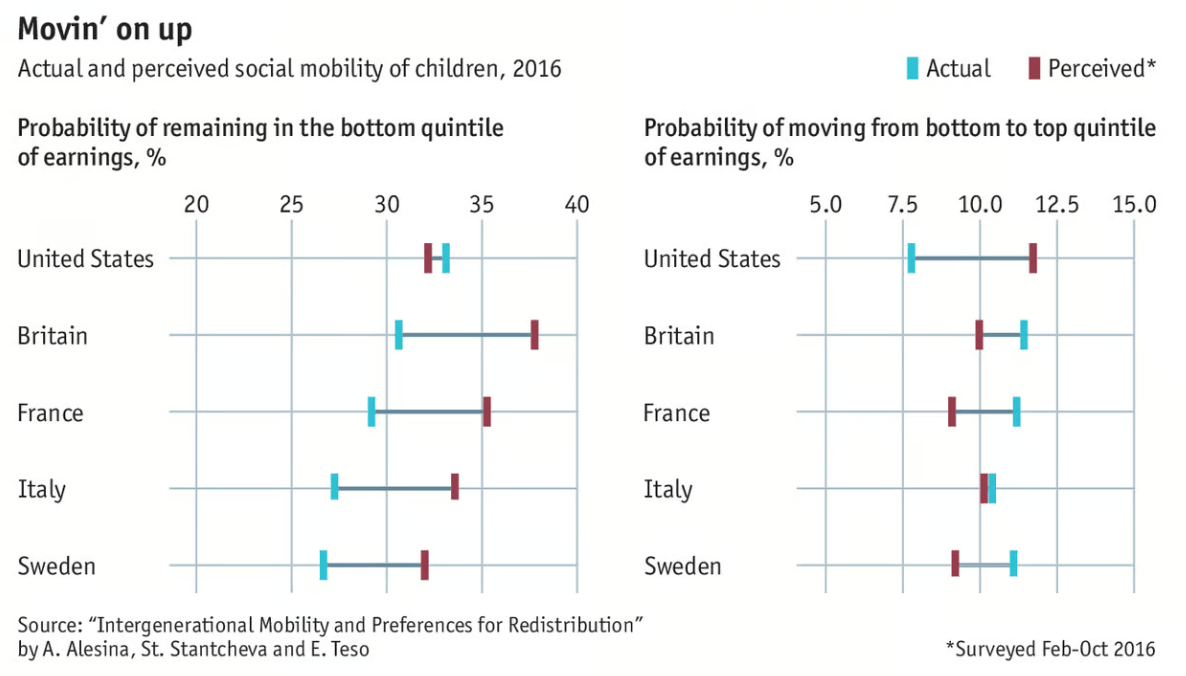

Since then, poverty rates have tumbled, wages have risen, and millennia-old barriers preventing class mobility have largely dissolved. Being born lower class is still a disadvantage, but it’s no longer a prison sentence. Still, despite these improvements over the last 70 years, poor citizens in most countries remain pessimistic about their chances of climbing from poor to rich. It’s tough to ignore 1,000 years of the Ancien Régime, I suppose, and this data is reflected in a Harvard study of perceived and actual social mobility in different countries:

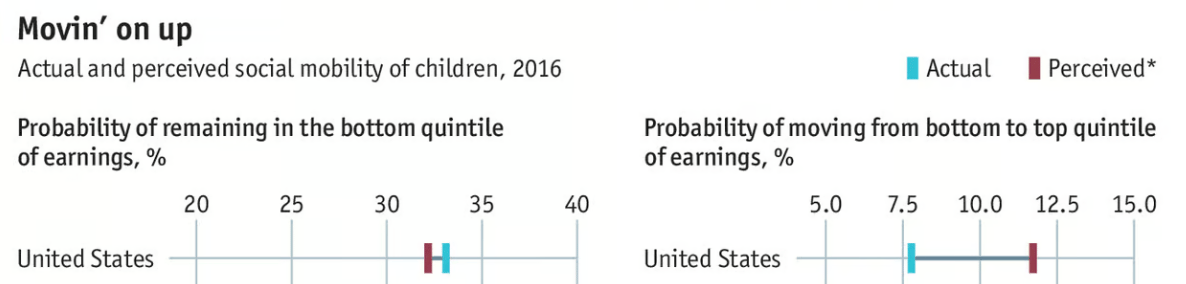

While most countries in this study underestimated their actual social mobility, there was one exception: America.

While most of the world is skeptical that they can improve their fortunes, Americans both overestimate their odds of climbing from the bottom 20% to the top 20% and underestimate their odds of failing to escape the bottom.

The American Dream is alive and well, baby, and our red-blooded optimism impacts our finances in two interesting ways.

1) The “Pre-Rich” Class

Because Americans are more inclined to believe they’ll escape poverty, many poor Americans don’t really see themselves as poor. Much like a VC-backed startup with $0 sales that calls itself “pre-revenue,” poor Americans subconsciously view themselves as “pre-rich.”

This belief that they will, one day, become rich causes many of the “pre-rich” Americans to identify with their wealthier, already rich counterparts, and this identity crisis gets interesting when taxes are involved.

Some common tropes in the “America vs. Western Europe” discourse are that Europe has a more robust social safety net, cheaper education, and widely available healthcare. European governments can provide these services because they have higher taxes.

Low-income Europeans, who tend to think that they will continue earning low incomes, happily benefit from the services funded by their countries’ higher taxes.

Many low-income Americans, on the other hand, oppose all tax hikes, possibly to their own detriment. Ramit Sethi, author of the best-selling personal finance book I Will Teach You to Be Rich, often highlights the absurdity of low-income Americans opposing tax increases that literally won’t affect them:

99% of the time, when a politician proposes to raise taxes, the increases would apply to billionaires, multi-millionaires, and/or corporations. Yet, Americans bringing home $48,765 who could stand to benefit from these very increases are up in arms.

It’s easy to label these Americans as irrational or misguided and assume they don’t realize that the increases wouldn’t affect them, but I don’t necessarily think they misunderstand the proposed changes. I think that because they truly believe they’ll climb the income ladder, they worry that a higher tax could impact their future selves.

This idea of being “Pre-Rich” also explains why we’re willing to go $100,000 into student debt (the European mind cannot comprehend this), and why we spend a disproportionate amount of our income on rent, clothes, travel, and other frivolous expenses: we’re banking on making enough money on the tail end to pay everything off.

Pre-Rich. It’s a fascinating concept, no?

2) Manifest Destiny

Is the American worse off because of his unbridled optimism? Looking back at the Harvard study, our behavior seems ridiculous, considering Americans overestimate their odds of climbing to the top quintile.

However, even if they don’t make it to the top, their optimism might still be valuable. The data from this study isn’t an apples-to-oranges comparison: it shows the odds of climbing from thethe top quintile in one’s respective country, and income ranges for these countries vary widely.

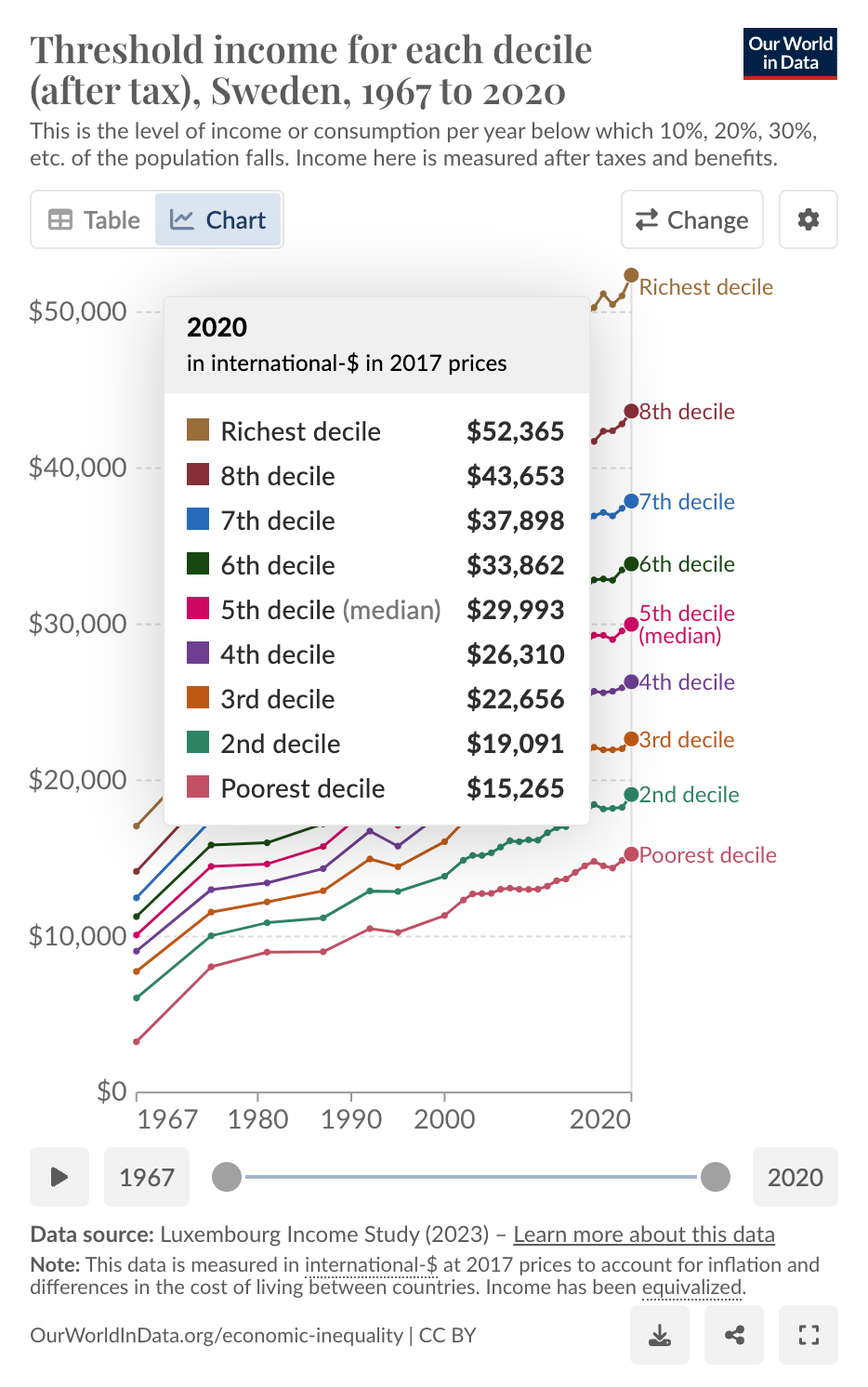

Our World in Data tracks inflation and currency-adjusted income deciles for our example countries

From these charts, the top and bottom income quintiles are as follows:

America: $71,885 vs $23,853

United Kingdom: $42,576 vs $17,579

France: $39,756 vs $17,620

Italy: $31,655 vs $11,634

Sweden: $43,653 vs $19,091

No wonder Americans overestimate their odds of climbing the wealth ladder compared to their European peers: making the jump from $17,620 to $39,756 in France is certainly easier than bridging the gap from $23,853 and $71,885 in America: it’s half the distance. That being said, even if you do fall short in America and only reach the US median income ($42,784), you’re still out-earning the top quintile in France (and the UK, and Italy, and ~almost Sweden).

Not bad!

Norman Vincent Peale once said, “Shoot for the moon. Even if you miss, you’ll land among the stars.” I’ve always thought that was a pretty stupid expression, considering the moon is much closer to Earth than any of the stars, but the point stands. Americans might underperform their income ambitions, but underperformance still lands them in a better spot than the highest 20% of earners pretty much anywhere else.

Maybe it pays to be an optimist.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

A couple of years ago, my friend Brian Luebben quit his 6-figure sales job to travel the world, and last month he published his book outlining how he did it, step-by-step. My personal favorite chapter covered "How To Build Your 100k+ Side Hustle,” and he’s sharing that piece with Young Money readers for free. Check it out.

Last week, I finished Nassim Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness, and it is just excellent. Give it a read.

I appreciated Packy McCormick’s 2023 reflection piece. The content game is tough, and it’s interesting reading through challenges that other writers are facing.